“… This longing for Light shows that I am right,

It tells me about another world, my real Native Land .

Does it have any meaning for people today?”

( Albert Camus, The Summer )

Let us, then, go to him outside the camp, bearing the disgrace he bore.

For here we do not have an enduring city, but we are looking for the city that is to come.

(Hebrews 13, 13’14 )

But our citizenship is in heaven. And we eagerly await a Saviour from there, the Lord Jesus Christ.

(Philippians 3,20 )

« Nostalgia », said a philosopher of Antiquity, « offers man lovely times and beautiful experiences ans memories which come from the past and which reality and the present cannot provide ». So, antiquity shows us the meaning and the content of this notion. But where does the term come from ?

Nostalgia (nostalgiva) is a Greek word ; we find it for the first time in the works of Homer (in Odyssey : « nostimon émar », « novstimon h\mar ») and then in the lyric poetry of the poetess Sappho. We find it also in the other poets, in ancient theatre and drama, and finally in the philosophical essays of Antiquity.

Philosophy as well as Philology defined the exact meaning of “nostalgia” : to have or to feel nostalgia for someone or something, and to feel nostalgic for someone or something. So today we use this word — especially after the influence of Romanticism — with the same meaning as in antiquity. In this way, nostalgia is a slightly sad and very affectionate feeling you have “for the past”, especially for a particular time ; eg. nostalgia for the good old days…, many people “look back” with nostalgia to feudal times…, he/she made me feel nostalgic…, and so on.

The English language, like the other languages of the world, uses the qualitative adjective “nostalgic” with an evocative meaning : “something that is nostalgic causes you to feel nostalgia”, like the sentimental meaning “someone who is or feels nostalgic is thinking affectionately about a happier time in the past”. In other words, nostalgia turns our minds “to the past”, to “look back”. That is the primitive philological or philosophical content of the notion “nostalgia” which today dominates the mentality of life.

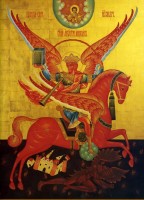

Photo by Dare, www.orthphoto.net

But the etymological analysis, which gives the exact content of the notion, is a little different from the philosophical definition. The word came from the Greek verb “nost-algw`” (“nost-algo”) : novsto” (=“nost-os”) and a[lgo” (=“algo-s”). “Nostos” signifies “yearning, craving, longing, desire, anxiety or wish”. “Algo-s”, verb and noun, signifies “suffer, feel pain, suffering, pain”. “Nostalg-o” as such signifies “I have a yearning with mental pain for someone or something”.

The languages which borrowed the term from the Greek adopted only the noun and the adjective, but not the verb nostalgw` (“nostalgo”), which expresses the first and the real notion of the word, eg. : “nostalgo” to return one day to my home/country — an action in the future which presupposes knowledge and experience (Maybe it is possible in English “to nostalgize” : “to yearn or long for someone or something” ! .)

From this analysis we can see that nostalgia concerns “perhaps” something in the future, or it is a more neutral term : we can use it for the future as well as for the past. But ancient philosophy put an emphasis only on “the past” of life, which all philosophy knows today in Europe and in the whole world. History and contemporary Romanticism did much in this direction. So, our thoughts turn “to the past” and “to the back”, while our way of life heads for the future, looking ahead…

History contributes sometimes to the cultivation of nostalgia, of historical nostalgia, but « the river does not flow back » (Greek popular proverb) : this nostalgia is eonistic, a principal parameter of Eonism. What has happened ?

It is true that this philosophical conception is very problematic, because it depends on the conception of time. In antiquity, the recycling of time was fundamental for philosophy. That is why the philosophers put this element of “recycling” into nostalgia. In fact, they charged it with a negative content with regard to life.

But this notion changed radically in the 4th and 5th centuries AD in the age of patristic Theology with the Cappadocian Fathers and then with St Maximos the Confessor. From those centuries until today, nostalgia concerns exclusively the future, the growth of every day… of every century… of every millennium… Nostalgia concerns something which comes from the future… In other words, nostalgia concerns Someone Who comes from the future… So, in the patristic perspective, “nost-algo” signifies “to desire (nostos) with pain (algos) to see/meet someone” who comes — who has already started to come — to me/us. (We are going and he is coming…). As we can see, the patristic nostalgia is not similar or different, but it is in the opposite direction, because it is eschatological… By the way, eschatological nostalgia acquires a special importance for life, and a dynamic content. It is very strange that the contemporary philosophers have not changed this content — as “lifestyle” (a way of living, a modus vivendi) — of ancient nostalgia and disregarded the notion of this evolution. (Did not they know ? Did not they want to ?…).

Now we have two nostalgias, the first characterized by escapism from reality and the second by dynamism for the present and principally for the future, waiting for action and decisiveness, in expectation and suspense for someone or something. The first relates to memory, the slightly sad, an unrealized desire, the imagination, etc.. The new nostalgia — with a new content, ontological content — does not like the escapism “to the past” and dislikes the memory’s “going back”… It looks fixedly at life and has eschatological content and perspective. Finally, the second has the same positive content as the etymological one : it has a direct and synonymous relation to “hope” and “expectation”. This nostalgia is for everybody and for peoples and especially for the young…

After this little essay, it is very clear that nostalgia concerns life itself, mankind and especially the young, because it gives to them an orientation and a direction in time, many perspectives and posibilities for action, an expectation for the future… Finally, this nostalgia can succeed in reviving the flat and flagging visions of every human person and humanity. In other words, eschatological nostalgia is proper for the existential perspective of humanity…

Prof. Hdr. Archim. Grigorios D. Papathomas, Dean of the St Platon Theological Seminar in Tallinn

Source: Orthodox Church of Estonia