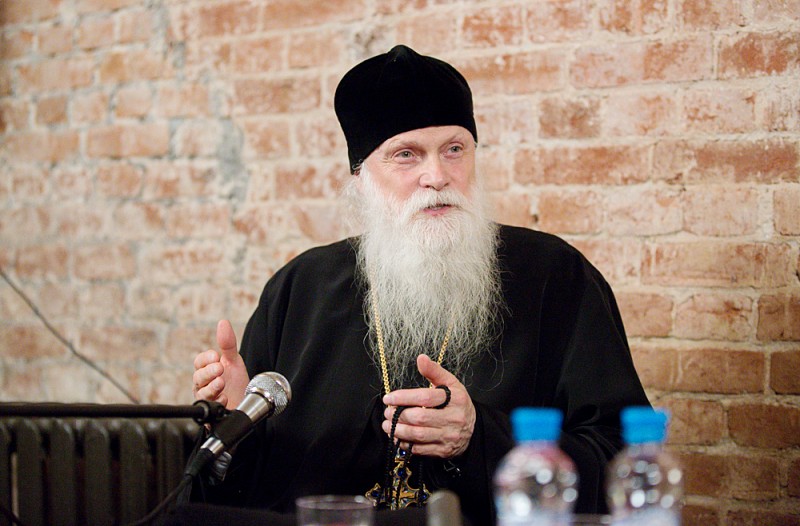

The following is translation into English of a talk recently given by Schema-Archimandrite Gabriel (Bunge) – a former Benedictine, a world-renown patristics scholar, and a hermit in the Alps – in the “kvARTira10” arts center in Moscow. The talk was given in French with Fr. Dmitry Ageev providing a translation into Russian; the present translation is from the original French. Next Sunday, God willing, we will provide a translation of the lively and extensive question-and-answer session that followed his presentation. A video of the event (in French and Russian) can be viewed here.

You’ve asked me to speak to you about prayer. It’s doubtlessly one of the most important subjects in a Christian’s life, because when one scrutinizes the Holy Fathers’ doctrine on prayer, one notes very quickly that the human person is only himself in the act of prayer. I shall return to this aspect.

Like everything else in life, prayer is a process that grows and evolves according to the rhythm of our human life. Therefore, I’d first like to speak to you about the ages of the spiritual life. I’ll base myself essentially on the teaching of Evagrius of Pontus, because I know him the best and also because he was one the first Desert Fathers to synthesize and put into writing the doctrine of the first monastic Fathers about prayer.

You might know that Evagrius was the disciple par excellence of Macarius the Great, who was himself the disciple of Anthony the Great. Therefore we are at the third generation of monasticism, which had already accumulated a rich experience. Thanks to his exceptional philosophical, theological, and spiritual culture, Evagrius was able to present the process of the spiritual life in a coherent manner. Evagrius had first been a disciple of Basil the Great, and then of Gregory the Theologian, and later in the desert – as I’ve already said – of Macarius the Great, as well as of other Fathers of this era. Thus, one simultaneously finds in him the stamp of the theology of the Cappadocian Fathers and the spiritual, and even mystical, experience of the Desert Fathers.

In a manner that might at first glance appear a bit unsophisticated, Evagrius defines Christianity as the doctrine of Christ our Savior that is divided into praktike [ascetic discipline], physike [natural contemplation], and theologike [theology].

Praktike is the practice of the Evangelical commandments. Physike – physis is “nature” – is the indirect contemplation of God by means of His works, of His creatures. Finally, theologike – theology – is the immediate knowledge of God Himself and coincides with what we today call, using a modern term, “mysticism.”

In modern terms, we can speak of three different ages because, as in normal physical life, we pass from one phase to another. Man progresses slowly but, contrary to normal physical life, there is nothing automatic between the various stages of the spiritual life. That is to say, many people remain their entire lives at the level of the practice of the Evangelical commandments.

The goal of this first stage or age – which is that of infancy or childhood – is to attain, with God’s grace, purity of heart. Therefore, this is a very important aspect, because one cannot speak of the spiritual life and of the following stages – contemplation of God, first indirect and then immediate – without purity of heart.

Thus, with the grace of God, man can arrive at purity of heart (this is also referred to using a term from ancient philosophy: apatheia), which itself has Christian charity as its daughter. Thus, freedom from the passions (apatheia) is the fruit of praktike, but also has a daughter: Christian charity (agape), which is the Christian virtue par excellence. This charity, Evagrius says, is the door to natural contemplation, that is, to the contemplation of God’s works.

But the next step or age – that of seniority or wisdom, of the contemplation of God’s works – is not arrived at automatically, because for man to be able to know God immediately, God must reveal Himself to him; He is free, He is a Person. He does so only when He judges man to be worthy of such a revelation.

All of this might seem a bit abstract to you, and you might pose some questions about it. But I think that it’s important in the spiritual life to know the road; not to believe, for example, that one can satisfy oneself for one’s entire life only reciting or listening to the Psalms or to conventional prayers.

You can also easily imagine that corresponding to these three ages of the spiritual life are three manners of praying. At first, man recites the Psalms and conventional prayers – which is, of course, excellent. But when he is called to ascend higher, when he contemplates the works of God, then his prayer, which had previously been supplication (as it is in the Psalms), becomes a prayer of praise. Man sings the praises of God for all that He has done. Then at the summit of this height something very mysterious takes place, about which one can no longer speak with the usual words and concepts. Evagrius does not do this; he speaks in Biblical images. This is a highly symbolic language, which one needs to known how to decode. And even if you have decoded it, ultimately you can understand exactly what it means only if you’ve had this experience.

But one can say – and Evagrius does say – that this is a dialogue or conversation with God without any intermediaries. What are these intermediaries? Above all, the creatures that speak about God, but aren’t God. These are the concepts that our spirit forges through its contact with reality. These are concepts or ideas about God, but which aren’t God.

I will stop here, but something very mysterious then happens, something in which God completely takes the initiative. Evagrius’ language on this subject is very significant: he speaks of manifestation, apparition, visit, et cetera, on God’s part. All this language indicates that there’s someone, the supreme Person of God, Who reveals Himself to His creature and makes Himself known and understood by him. But the curious thing – which is where I’ll stop – is that the man who has reached this stage is not conscious. The contemplative – the one who sees God – is, as it were, in a state of sleep. When we sleep, we do not know that we’re asleep. Thus, curiously, the contemplative doesn’t know; he finds himself in an entirely peculiar state; he is here and is not here. He isn’t conscious. It’s not ecstasy, in which man goes out of himself or where he loses his consciousness. It’s nothing like that.

I will conclude this short exposition with a word from the Curé d’Ars, whom you might not know. He was a French priest of the nineteenth century, a saint of the Catholic Church. One day he found an old man, an old peasant, in his church, sitting on a bench and not appearing to be doing anything; he wasn’t even praying the rosary. He asked him: “What are you doing here?” In his old French, he said: “I’m looking at Him; and He’s looking at me.” That is the mystery.

Pravmir wishes to express its thanks to Subdeacon Claude Lopez-Ginisty (of http://orthodoxologie.blogspot.com) for his assistance in translating this talk from the French.