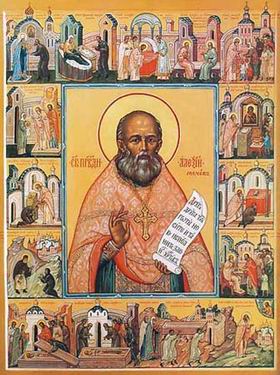

Father Alexey Mechev

Fr. Alexey was born in 1860, the son of a choir director in the service of the great Metropolitan Philaret of Moscow (†1867). The family lived in modest circumstances. “I never had a room of my own,” Fr. Alexey recalled. “All my life I’ve lived with people around!” Judging from the only extant letter to his wife Anna, he was happily married; they had several children before her tragically premature death. None of the children appear to have remained close to their father with the exception of a son Sergius who succeeded Fr. Alexey as priest at St. Nicholas’ church on Maroseyka street, before joining the ranks of Russia’s New Martyrs in 1941.

Fr. Alexey was born in 1860, the son of a choir director in the service of the great Metropolitan Philaret of Moscow (†1867). The family lived in modest circumstances. “I never had a room of my own,” Fr. Alexey recalled. “All my life I’ve lived with people around!” Judging from the only extant letter to his wife Anna, he was happily married; they had several children before her tragically premature death. None of the children appear to have remained close to their father with the exception of a son Sergius who succeeded Fr. Alexey as priest at St. Nicholas’ church on Maroseyka street, before joining the ranks of Russia’s New Martyrs in 1941.

Fr. Alexey’s success did not blossom overnight. Describing the early years of his pastorate he said: “For eight years I served the Liturgy daily in an empty church. One archpriest said to me: ‘No matter when I pass by your church, the bells are always ringing. Once I went in – nobody. Nothing will come of it. You’re ringing in vain.” But Fr. Alexey steadfastly continued serving and the people began to come, many people. He would tell this story when asked how to establish a parish. The answer was always the same: “Pray.”

In his domestic life batiushka was extremely simple and humble. In his study, in his little room, there were piles of books – some lying open, letters, lots of prosphora on the table, a folded epitrachelion lying together with a cross and Gospel, and little icons. The general chaos indicated that Batiushka was always busy, that he never had spare time, that there was always waiting for him at home, on the street, in church – some great task calling for his love and self-sacrifice.

![]() “Live for others, and you yourself will be saved.” This was Fr. Alexey’s motto. “To be with people,” he would say, “to live their life, rejoice in their joys, sorrow over their misfortunes.., herein lies the meaning and way of life for a Christian, and especially for a pastor.”

“Live for others, and you yourself will be saved.” This was Fr. Alexey’s motto. “To be with people,” he would say, “to live their life, rejoice in their joys, sorrow over their misfortunes.., herein lies the meaning and way of life for a Christian, and especially for a pastor.”

Fr. Alexey’s own life was consumed in the service of others. Outside his apartment the line of laboring and heavy-laden’ stood from early morning. And Batiushka managed to have a talk with each of them, to caress, to console. Never was he ever alone. He was always with people, and in sight of people; it was as though the walls of his room were glass – everything was visible.

Fr. Alexey often said that “each person has his own particular path to salvation. One mustn’t set a common path for everyone; one mustn’t try to workout a formula for salvation which would apply to all people. People are born with different natures, different abilities, intellects and constitutions – so, too, they each go towards Christ at their own pace, each on his own path.

Because of this, Christianity considers equally soul-saving the chaste monastic life and marital life, the priesthood and laity, the rank of soldier and the rank of judge – as long as Christ dwells in the heart. And the task of an elder or a spiritual father is to uncover a person’s calling and to point out to him the path which he should take towards the Lord.”

Because of this, Christianity considers equally soul-saving the chaste monastic life and marital life, the priesthood and laity, the rank of soldier and the rank of judge – as long as Christ dwells in the heart. And the task of an elder or a spiritual father is to uncover a person’s calling and to point out to him the path which he should take towards the Lord.”

With his gift of clairvoyance, Fr. Alexey had no need to speak to his “patients” in order to diagnose their maladies. And his “treatments” showed this masterful physician to be a man “not of words, but of spirit, of power”: “It seemed that Batiushka didn’t really say much; from his face alone, his smile, his eyes, there streamed such gentleness, such understanding, that this in itself comforted and encouraged a person without any words. …He actually, as he himself put it, ‘unloaded’ people’s sins; he transformed people from despairing, oppressed pessimists into Christians constantly rejoicing in the Lord. One had only to glance at his commemoration book, checkered with hundreds of names of both living and dead, a book he always had with him, and one understood the words which he spoke, pointing to his heart: “I carry you all here.”

The scope of Fr. Alexey’s pastoral influence may be judged by the tens of thousands who gathered for his funeral. The liturgy was served by Bishop Theodore Pozdeyev (later, archbishop and New Martyr), attended by 80 clergymen – hierarchs, priests and deacons. The imprisoned Patriarch Tikhon, freed for a few hours, met the cortege at the St. Lazarus cemetery, where he served a lity for the deceased. Altogether, it was a fitting tribute to this remarkable pastor who had been, for so many, a stepping-stone to God.

Father Alexey, pray to God for us!

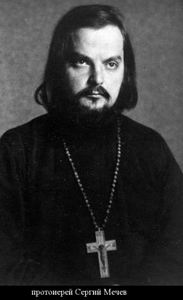

Father Sergius Mechev

Thousands mourned the death in 1923 of the popular, clairvoyant lay-elder of Moscow, Archpriest Alexey Mechev. But the Lord did not leave his spiritual children orphaned. Many had already discovered in his son, the still young Priest Sergius, a worthy and equally gifted successor.

Thousands mourned the death in 1923 of the popular, clairvoyant lay-elder of Moscow, Archpriest Alexey Mechev. But the Lord did not leave his spiritual children orphaned. Many had already discovered in his son, the still young Priest Sergius, a worthy and equally gifted successor.

The Saint Nicholas parish on Maroseyka, where his father served, was still small when the future priest and new martyr, Sergius, was born on 17 September 1892. He was the fourth child and arrived in a household that was already cramped for space and pinched financially.

The frequent shortage of food was at fault for the boy’s weak constitution, but he had a strong-willed character inherited from his mother, Anna Petrovna. Her death in 1901, was hard on him, but fortunately he had a close bond with his father, who was tenderly affectionate and even years later, in his letters, continued to address his son endearingly as “Sergunchik,” signing them, “with many kisses from your papa who loves you.” Fr. Alexey saw in his son his successor, but he felt the boy should choose his own path, and for that reason declined to send him to a diocesan school, where students were expected to become priests.

Instead, Sergius received a secular education at a regular school, and received his religious training at home and in church, principally by observing his father in the altar. Upon graduating, he fulfilled a dream by taking a trip abroad, to Switzerland and Italy, and then entered the medical faculty at Moscow University. Although he later transferred to the philology department, he acquired sufficient knowledge to work as a nurse at the front when the war came.

![]() There he met his future wife, Evfrosinia Nikolaevna. They were married in 1918. While Fr. Sergius had still not made up his mind to enter the priesthood, he was active in the Church; he participated in a student theological circle and avidly studied patristics. As a member of a commission formed to negotiate relations with the new government, he came into frequent contact with Patriarch Tikhon, who became very fond of him and urged him to become a priest. His decision to do so was inspired by a discussion he had with Elder Anatole of Optina in the fall of 1918. The following April, on Holy Thursday, he was ordained by Bishop Theodore Pozdeev at St. Daniel’s Monastery.

There he met his future wife, Evfrosinia Nikolaevna. They were married in 1918. While Fr. Sergius had still not made up his mind to enter the priesthood, he was active in the Church; he participated in a student theological circle and avidly studied patristics. As a member of a commission formed to negotiate relations with the new government, he came into frequent contact with Patriarch Tikhon, who became very fond of him and urged him to become a priest. His decision to do so was inspired by a discussion he had with Elder Anatole of Optina in the fall of 1918. The following April, on Holy Thursday, he was ordained by Bishop Theodore Pozdeev at St. Daniel’s Monastery.

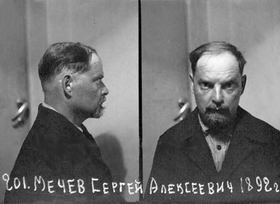

Fr. Sergius served at the Maroseyka church until his arrest in November 1929. Like so many clergy, he did not recognize Metropolitan Sergius’ Declaration of 1927, which essentially brought the Church under government control. He was charged with heading a counter-revolutionary underground church and sentenced to three years’ exile in the far north, near Arkhangelsk. His matushka managed to visit him with their three children (another had died in infancy), and he kept in touch with his spiritual children, writing to them individually and addressing five letters to them in common, letters that have been preserved. It was several months after his term had expired that Fr. Sergius was finally released; he was never free again.

A second arrest followed in March 1934, carrying a five-year sentence. He spent some years in hiding, wandering from place to place, before being arrested yet again. The spiritual daughter with whom he was imprisoned reported that he was almost certainly executed in early November 1941; elsewhere, his martyric death is commemorated December 9. Fr. Sergius entered the ranks of Russia’s New Martyrs for his uncompromising stand in ecclesial matters. His principal renown, however, rests upon his pastoral skills. The Maroseyka parish was unique in Moscow in cultivating an inwardly monastic orientation. Fr. Alexey often said that his task was to create “a monastery in the world,” by which he meant a parish family guided towards the same goal of sanctity and deification as the monastic.

A second arrest followed in March 1934, carrying a five-year sentence. He spent some years in hiding, wandering from place to place, before being arrested yet again. The spiritual daughter with whom he was imprisoned reported that he was almost certainly executed in early November 1941; elsewhere, his martyric death is commemorated December 9. Fr. Sergius entered the ranks of Russia’s New Martyrs for his uncompromising stand in ecclesial matters. His principal renown, however, rests upon his pastoral skills. The Maroseyka parish was unique in Moscow in cultivating an inwardly monastic orientation. Fr. Alexey often said that his task was to create “a monastery in the world,” by which he meant a parish family guided towards the same goal of sanctity and deification as the monastic.

Fr. Sergius held the same principle although later on he stopped speaking of it as a “monastery in the world,” because others had adopted this term as meaning some kind of community of secret monks or nuns who lived in the world while under obedience to monastic vows. Instead, Fr. Sergius took from ancient Russian church practice the term “repenting family.” He also referred to his parish as a “repenting-liturgical family.” It was very apt. As a spiritual director, he strove to cultivate in his flock a spirit of repentance and he encouraged frequent attendance at church services, which he considered to be the best school for the development of spiritual life. The excerpts that follow illustrate his effective approach.

Father Sergius, pray to God for us!