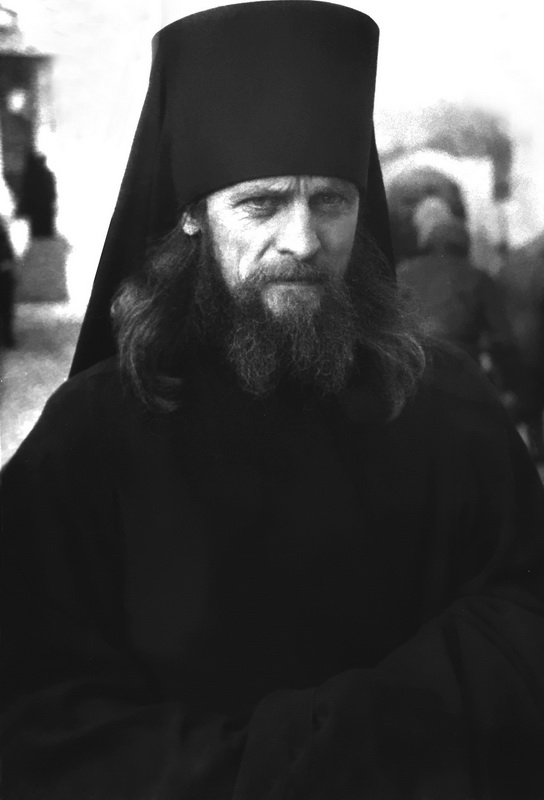

On April 18, 1993, three monks were slain during the Paschal night in Optina Pustyn: Hieromonk Vasily (Roslyakov, b. 1960) and Monks Ferapont (Pushkarev, b. 1955) and Trophim (Tatarnikov, b. 1954). George Gupalo, who knew all three monks and was there on the night of their slaying, offers the following recollections.

Twenty years have flown by since the slayings in Optina Pustyn, when three good men died and three holy martyrs were born. I happened to be in Optina then, to see the death of Fr. Trophim, and to lower the three coffins into the damp spring earth of Kaluga. Much has happened in the ensuing years, but it seems to me that I can recall in detail every moment of that tragedy, since it shook all the witnesses.

My short account will be about several moments of that great day.

I no longer lived in Optina, but had come for a visit on Pascha. The evening before Pascha was quiet and beautiful: the setting of the red sun, spreading lovely, warm colors, had nothing foreboding about it. It was even strange that, despite the redness of the sunset, it could not be called sanguinary, so gentle and pleasant was it to the eye. Nothing boded trouble, although the trouble was already nearby, near each one of us. The killer had prepared his crime and was only waiting for a push from the “voice that he could not disobey.” He was in Optina, nearby, very close, looking for his prey. But no one knew about this, no one had any idea about this.

Strolling around the monastery, I noticed Fr. Vasily leaving the Cathedral of the Entrance. He was standing at the northern entrance to the church admiring the beauty of the sunset. And I, in turn, stopped and began to admire the picture with him included: beside the snow-white church stands a beautiful monk. Russian, slim, athletic, quiet and peaceful, wise beyond his years, clearly the future glory of Optina.

Many years later he will become even wiser and more experienced. Thousands of people will come to him for advice and consolation. He will become a new Optina Elder. After all, we had been promised that there would be seven luminaries. Perhaps he will be one of them. “Oh, how good he is, this warrior of Christ,” I thought. “May God grant, my dear, that you not leave your path, that you remain a man, and that you amass wisdom and love, bestowing them upon God’s people.” Fr. Vasily, sensing that someone was watching him, turned around, smiling when he saw me. We had not seen each other for some months. We exchanged bows from a distance and decided to maintain our quiet state. But his smile, his radiant smile, sunk into my memory and will now live with me until my very death.

The service began. The monastery brethren entered the church, Fr. Ferapont among them. No one befriended Fr. Ferapont. This was by no means because he was a mean or bad person. This was simply because, in spite of his relative youth and early monasticism, he had managed to become a true monk: he did not belong to any of the groups or circles of interest that often form in monasteries, but lived a very hidden and true monastic life, without quarrels or conflicts, without empty conversations over tea or gossip during obediences. The life of such monks is usually described by the beautiful Russian word sokrovennyi [hidden], as stated in the Epistle: But let it be the hidden man of the heart, in that which is not corruptible, even the ornament of a meek and quiet spirit, which is in the sight of God of great price (1 Peter 3:4).

Fr. Trophim entered the church. He was a bit late to the service, inasmuch as he worked a great deal in the housekeeping area. From morning until late in the evening he could be seen either on a tractor or on a rototiller. He was always joyful, energetic, and incredibly alive – the complete opposite of the secluded and silent Fr. Ferapont. Around Fr. Trophim life was always seething and work was in full swing. He had many friends; he was a very sociable and upbeat person. He approached the left kliros [choir], where I was standing, smiled his open smile, and we warmly hugged and exchanged kisses. A quick exchange of news, firm handshakes. Who knew that in a few hours he would no longer be among the living? Lively, energetic, cheerful. Well, he could not die young. He still had many, many years ahead of him. But man proposes, and God disposes.

Thus have these three smiles stuck in my memory. So different, but each so beautiful in its own way. Later there were different smiles, and they were imprinted even more firmly in my memory.

The Paschal Liturgy came to an end. All the brethren went to the refectory, broke the fast, the majority went to get some rest, and the bell-ringers Trophim and Ferapont went to the bell-tower, but Fr. Vasily went to the Liturgy at the skete to confess people. I was in the skete at this time, resting in the cell of the skete superior. The Liturgy in the skete had just begun when there was a knock at the door. The knocking became more insistent and I decided to open the door. In the doorway stood the guard of the skete’s guesthouse in a terribly nervous state. He told me that there had been a murder in the monastery – that some monks had been killed. He had gotten a call from the monastery guardhouse and been asked to warn the skete superior and all the brethren of the skete. I brought the guard to church, while I gathered my things and went to the monastery. There was something absurd about the news: how could there be a murder in the monastery, in Optina?! This was obvious nonsense and someone’s sick joke. Who could have known that the killer was on the footpath with me at the same time, only hiding in the bushes and headed in the other direction?

Optina was quite deserted. No one could even have seen the killer, since everyone had left. Having heard of the crime, the brethren began to assemble. The first thing I saw was Fr. Ferapont. He was lying on the belfry, pierced through by a short sword constructed from automobile shocks. As it later turned out, “working” with such a weapon is very difficult – one needs to possess either enormous strength or a great deal of training.

The killer, Averin, was puny, but here he was clearly assisted by man’s true and eternal killer. Only this inhuman strength can explain the strength of Averin’s blow: in addition to the body, the leather monastic belt was pierced in three places. After inflicting a single blow right in the liver, he dropped Ferapont’s body to the ground and covered his head with his klobuk. He himself could not explain why he did this. He then quickly got up and, with a second blow, fatally wounded Fr. Trophim. He did not even manage to understand what was going on: both monks were standing almost back-to-back to one another and Trophim did not see what happened. He only heard that the ringing had stopped and turned to face his companion, but it was already too late – the cold, bloodied blade pierced his liver. Averin also dropped Trophim, also covered his head with his klobuk, and then calmly walked toward the skete, on the heels of Fr. Vasily. A third blow, and a third person fell to the ground. Then the killer ran behind the house near the skete tower, cast his terrible sword there, climbed over the fence, and ran into the woods. Three female pilgrims could only make out a fleeing figure in a gray overcoat. There were no more traces or marks (apart from the sword). But by the third day an ambush was waiting for Averin at his home and a manhunt was underway in the nearby woods. (Since then I have known for certain that if our authorities want to solve a murder, then can do so quickly. They can do this (and they could then) if they want to.)

I did not see the murder itself, but Fr. Trophim gave up his spirit in my arms. His face was full of sorrow and pain. It was evident that he was experiencing great suffering. He departed quietly. He simply froze – and that was all. Fr. Vasily survived the longest, dying in the ambulance on the way to Kozelsk. His athletic body did all it could to resist death, but the wound was too terrible.

Later the police arrived, operative actions began, and all the dead were taken away for post-mortems. After a few hours they were brought to the Church of St. Hilarion. As far as I can remember, I was the only layman present at these first prayers at the bodies of the slain brethren; I saw their bodies while still uncovered, without vestments. According to tradition, laymen are not supposed to be present at the vesting of monks, but an exception was made for me. And I am grateful that I was present at these prayers. Believe me, I have never again seen or felt anything like it. First of all, one should say something about the faces of the slain brethren.

Do you know what struck me then? All three died in terrible agony, from unimaginable pain, and at the time of death this pain remained on their faces. But then a few hours passed and I saw completely different faces. They could even be called iconic countenances [liki], they were so bright and luminous. This was not just my exalted perception: everyone noticed the strange transfiguration of their faces. There was a bright, quiet, and peaceful smile on all of them. Very reposed and confident. There was the sense that they had seen something joyful. The surprising thing is that the spirit left the body, but transformed it after death. These are the three smiles of which I spoke at the beginning of my account. It is these smiles that I shall never forget. Here is clear evidence of the existence of the afterlife.

It is hard to convey in words the state of the monastery brethren. I think something similar must have been experienced by the Apostles after Christ’s execution and by the disciples of the Optina Elders after the latter’s deaths. On the one hand, horror over what had occurred and the bitterness of parting; but, on the other hand, joy for their brethren. After all, they were now all at God’s Throne. They began celebrating Pascha on Earth and completed it in Heaven. And we believe that their Paschal joy will be eternal there. They earned it by their earthly life, being vouchsafed to accept the crown of martyrdom.

That evening many spoke these words: I was not found worthy, due to my sins.

+++

Before writing these short recollections, I found a transcript of the speech given by Hieromonk Theophylact of Optina at the funeral service of the slain Optina monks. I do not know how accurate the transcript is, but it is very faithful in substance and goes a long way to convey our experiences of those days:

“Today we are performing something unusual, miraculous, and wondrous… Every Christian who is well acquainted with the teaching of the Church knows that one does not just die on Pascha, that there is nothing accidental in our life. To go to the Lord on the day of Holy Pascha is a special honor and mercy from the Lord. From the day on which these three brethren were slain, the bell toll in Optina Pustyn has sounded different. It heralds not only the victory of Christ over the Antichrist, but also that now the earth of Optina Pustyn has been abundantly watered not only with the sweat of ascetics and monks, but also with the blood of Optina brethren. This blood is a special protection and testimony for the future history of Optina Pustyn. Now we now that we have special intercessors before God’s Throne.”