Following destruction of ‘Albania’s Sistine Chapel’, state officials say they don’t have the ability to protect all of the country’s heritage jewels

Following destruction of ‘Albania’s Sistine Chapel’, state officials say they don’t have the ability to protect all of the country’s heritage jewels

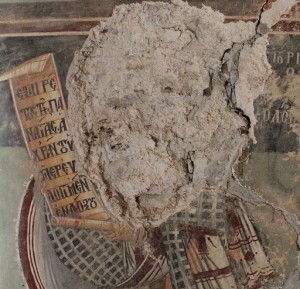

TIRANA, Jan. 10 – The medieval frescoes of St. Premte Chapel in central Albania survived the Ottoman Empire, various uprisings, two world wars and the world’s only officially atheist regime — but they could not survive one or more amateurish thieves who tried to chisel them out of the wall in the evenings of Dec. 30 and Jan. 4.Most of the frescoes at the small church in southeastern Elbasan County were the work of Onufri, a painter of the 1500s considered to be Albania’s Michelangelo for his work on Orthodox churches in central and southern Albania.The attempt to steal the frescoes has made irreparable damage to the historical site, authorities say.Gifted with a great wealth of cultural damage, post-communist Albania has seen a trend of destruction and theft at its cultural monuments in the past 20 years. Experts say investment, better infrastructure, tougher punishments and more education are needed to to protect the country’s historical, cultural and art heritage.

Site unguarded, authorities slow to respond

St. Premte Chapel is located in a very rural mountainous area in the Shpat region of Elbasan County. Its walls are covered in Biblical depictions of the Virgin Mary and various saints, including that of St. Premte, an indigenous Albanian saint whose name is carried by several Catholic and Orthodox churches across Albania. The Onufri paintings were dated at 1554 and contained an inscription by the author, which is now gone.On Dec. 30, the chapel was closed and unguarded, and it took some time for state and church authorities to be notified by the area’s local residents who first discovered the damage. But the local media reported the authorities were very slow to act, which allowed the thieves to return to the site on a different night and do more damage.

Authorities have yet to identify the authors, but experts say they were likely amateurs.

“They used none of the tools a professional would use to dismount art works like these,” said a Culture Ministry official.

The thieves used an ax-like tool to go after the heads of the saints in the frescoes, leaving behind the bare walls. Many of these parts were taken — likely for illegal sale — and some were left destroyed because they had crumbled on the floor. It is the fact that the chiseled paintings were taken away from the church that has led authorities to believe they are dealing with thieves rather than vandals or something more sinister, like a religious hate crime.

Activists demand accountability

Two heritage experts, Artan Shkreli and Auron Tare, traveled to the area after they heard of the incident and notified the media of what had happened, accusing authorities of trying to keep the damage quiet and demanding accountability.

Shkreli, who heads the Forum for the Protection of Heritage, told the local media this is possibly the worst crime of its type to Albania’s cultural heritage in the past 20 years.

“In a way, this is the Sistine Chapel of Albanian frescoes, one of the most extraordinary scenes in all the manuals of medieval Albanian art,” Shkreli told the local media.

Tare said the Onfri frescoes, in the Albanian context, are as important as those Michelangelo and Da Vinci to Italian heritage.

“Some has to be held accountable … The Culture Minister and the Director of Heritage should resign,” Tare, who is also an opposition MP, told the Gazeta Shqiptare newspaper.

The activists are calling for far tougher punishment of those who damage or steal from cultural heritage sites, pointing out that prosecutions and punishments have been rare and have not served as a deterrent.

Authorities say they lack resources, infrastructure to protect rural monuments

Olsi Lafe, who heads the heritage department at the Ministry of Culture, said in a press conference that his institution simply does not possess the money and infrastructure to protect all cultural monuments 24 hours a day.

“We manage a very large territory. Given that the number of monuments is large and many of them are located in very rural areas, away from residential centers, it is impossible to control them 24 hours a day,” Lafe said.

Lafe added the ministry is working with police to apprehend the people who caused irreversible damage to the church and Albanian medieval art heritage.

Theft highlights fate of Albania’s cultural heritage

Heritage experts that work for the government and civil society institutions say this is a grave incident which is part of a trend of destruction and theft of Albania’s cultural heritage in the past two decades.

They say investment, better infrastructure and tougher punishments are needed — in combination with better education for the population at large on how to protect and value the share heritage of the community.

Albania, which for hundreds of years has been at the crossroads of different cultures, has a vast wealth of cultural heritage, much of which is known and appreciated worldwide.

Due to Albania’s difficult post-communist transition, many international institutions and the embassies of the several EU countries have offered funding to reconstruct monuments of culture in Albania. In fact, much of the reconstruction work that has taken place in large and small heritage sites has been done thanks to funding provided by UNESCO, governments of EU members states and the other friends of Albania.

But experts note taking local ownership is very important and providing proper education and manpower to protect and restore monuments is imperative.

Available options for the future discussed

Lafe said the ministry needs the help of the religious communities (in this case, the Orthodox Church) and the public to protect such monuments. He also added it needs more funding, pointing to requests made to the Ministry of Finance in the past.

But Lafe underlined that the ministry needs an entirely different infrastructure in the place if it were to protect all monuments across Albania from such damage.

Apollon Bace, the head of the Institute of Monuments, the state body charged with protecting and restoring moments, told the local newspaper Mapo that ideally a system of overseers should be in place to protect each monument, a variation on the system used before the fall of communism. An overseer is a semi-volunteer position where the state pays a small sum every month to a local inhabitant to keep an eye on the monument and the area around it.

Others say local authorities should interfere, creating a regional system of protection brigades that doesn’t entirely depend on the central government.

“The local government should definitely have a guard at these monuments of culture. But these mountain municipalities have no funding to do so,” Kristaq Shqau, head of the Gjinar Commune, where the chapel is located, told private television channel, Albanian Screen.