The poet Joseph Brodsky kept a wonderful tradition: for several years in a row on the eve of the Nativity of Christ he composed “verselets” [stishki] (as he called them) dedicated to this event. Brodsky called himself an unbeliever and said that if he could choose his own religion, he would likely be a Calvinist – someone responsible for his actions to God alone.

Nevertheless, it turns out that this Nobel Prize laureate in Literature was able to express in verse the feelings that make the Nativity a favorite holiday of many Christians very accurately. It goes without saying that this is a favorite holiday not only because of long vacations and presents (although these are certainly very nice), but rather because this might be the event in the Gospels in which God appears the most defenseless.

The God-Man’s entire earthly life was still ahead of Him; for now He was just a Child born at an inconvenient time. Over the past nearly two thousand years we Christians have become so accustomed to celebrating His Nativity that we might not give sufficient thought to what actually happened on that day.

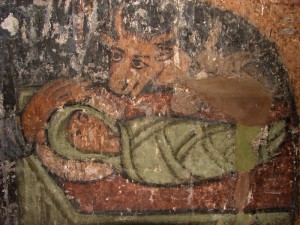

Metropolitan Anthony of Sourozh, in speaking about Good Friday, said that we have come to regard the tragic events of human history as beautiful performances. Lulled by the beautiful words of the Slavonic services, we forget that the circumstances of the God-Child’s birth were frightful. Octavian Augustus was conducting a census of the population that unwillingly returned thousands of people to the cities and villages in which there were “inscribed,” disrupting their usual way of life. Among this crowd of poor people, unwillingly displaced across the Roman Empire, were the Mother of God and Joseph the Betrothed, whom no looked upon as holy. Rather, they looked very much like those troublesome beggars who knocked at people’s doors asking for bread, money, and clothing.

In our days there are few who would open their doors to such people, and it is entirely unimaginable that someone would allow an unknown man and a pregnant woman into their home so that she could deliver a child. At best we might call an ambulance. Manger and cave are not cheerful symbols, but rather terrible symbols of that ordinary human indifference that each of us faces periodically. From the very moment of His entry into our world, Christ did not look for the “easy way out.” We can therefore have faith that He understands the everyday problems and difficulties of everyone who turns to Him in prayer.

I myself have a very personal reason to love the Nativity. Nearly five years ago, at the end of December and beginning of January, I fell completely in love with the young woman who was to become my wife. The brightest Nativity service of my life took place in 2008. I went on crutches to the crowded little church near my home, was given a stool on which to sit through the service, and then returned home. At three in the morning a water hose on the gas heater burst. For the first time in our lives we flooded the neighbors’.

From that point on, everything happened just like in a Christmas story. Repairmen quickly arrived to attach a cover and the neighbors would not accept money from us to cover damages. Simply put, on Christmas night miracles do happen on this earth.

Every reader of this column will likely be able to recall his own “Christmas stories” that took place on the eve of the celebration of the Savior’s coming into the world. But that is still not the most interesting thing. On January 7 many of us will go to church or will meet the Holy Night at home with our families. Everyone will have his own expectations and associations, but we will be united by the same joyful feeling of meeting Christ. But with this joy will mingle that tragic grief about which Metropolitan Anthony (Bloom) spoke so well: “Alas, to this day how many people there are in large cities and over the vast expanses of the earth who have nowhere to go, who have no one waiting for them, for whom no one sighs, to whom no one is prepared to open his home, since they are strangers or because it is terrible to share the fate of people who have been made miserable not only by unhappiness, but also by human malice: they have become strangers because other people have excluded them from their hearts and fates. Loneliness – that terrible, searing, devastating loneliness that consumes the hearts of so many – was the lot of the Most Pure Lady Theotokos, Joseph the Betrothed, and the newborn Christ.”

I am not going to call upon the readers of this column to help the disadvantaged, since I have no right to do so. But I very much hope that, in honor of the Nativity, we will strive to do everything we can so that our family and friends might not feel lonely. If we Christians can manage – for a day, a month, or even an entire year – to give at least the people closest to us the feeling of being wanted, loved, and needed, then perhaps by next Nativity there will be a door through which a stranger in need of help and support can enter. If this comes about, then the words written by Virgil several years before (!) Christ’s birth – “Only do you, pure Lucina, smile on the birth of the child, under whom the iron age shall at least cease and a golden race spring up throughout the world” [2] – will finally be realized, and a less brutal age will ensue.

Translated from the Russian

Translator’s notes:

[1] The opening lines from Brodsky’s “Nativity 1963.”

[2] From Virgil’s Eclogue IV.