Source: In Communion / Summer 2010 / issue 57

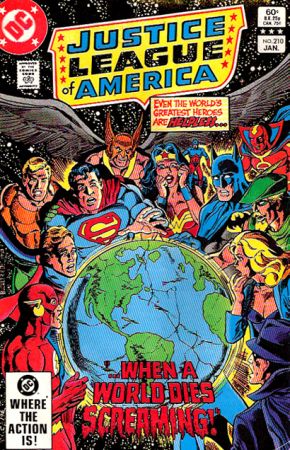

When I was a kid, there was a comic book series called “The Justice League of America.” Its members included Superman, Batman, Wonderwoman plus some lesser-known superheroes. The outcome of each confrontation was that the innocents were saved and the “bad guys” got “what was coming to them.” In fact, this was the never-varying plot-line of Dragnet, Zorro, the Lone Ranger and indeed all the fantasy worlds kids inhabited in those days. Justice triumphed, evil-doers were punished.

When I was a kid, there was a comic book series called “The Justice League of America.” Its members included Superman, Batman, Wonderwoman plus some lesser-known superheroes. The outcome of each confrontation was that the innocents were saved and the “bad guys” got “what was coming to them.” In fact, this was the never-varying plot-line of Dragnet, Zorro, the Lone Ranger and indeed all the fantasy worlds kids inhabited in those days. Justice triumphed, evil-doers were punished.

We’re not kids anymore. Our worldview isn’t shaped by comic books. We’re old enough not to see mutual destruction or the triumph of the powerful as desirable outcomes in human conflicts. We tend to think in terms of peace and justice. But here lies a tension. Is peace the goal? Or is justice our priority? Or shall we glue them together into “just-peace” – a hybrid word that welds justice and peace together, like yin and yang, inseparable segments of a whole?

Looking back on my initiation into American superhero justice, I am reminded of one of the dialogues of Socrates with his young colleagues in Book One of Plato’s The Republic. Plato presents (in the words of editor Benjamin Jowett), “a refutation of popular and sophistical notions of justice” (such as doing good only to one’s friends, justice as the interest of the stronger, etc.). In the process, Socrates questions the definition of justice as “everyone getting his due” – pleasant rewards going to the virtuous and negative consequences being meted out to the evil. Sounds like what most people mean when they say “justice.”

For Plato, justice was “based on the idea of good, which is the harmony of the universe.” Now Christians believe that “The Good” equals God and that the harmony of the universe is the peace of Christ. Therefore, “giving to each man what is proper to him” might include a good deal more than what usual human standards have regarded as appropriate.

If we Christians believe that each person is a bearer of the image of God, and that our ultimate destination is to be with God in heaven, then the concept of “what is due” each of us expands considerably.

Looked at this way, God asks much more of us than the promotion of human justice. If we give each “his due” – thinking about this in the usual constricted and grudging sort of way, then we are in danger of being like the persons mentioned in Luke 6 about whom it was said “even sinners love those who love them.” That is, even a non-believer might be willing to say that everyone should get what is due him, if they mean only a juridical type of “due-ness.” We, however, are bound to make the definition of the word “justice” subsume all that our instruction in the faith would lead us to include in it, the fullness of justice, if you will.

St. Isaac the Syrian actually made this distinction between God’s grace and man’s justice when he counseled, “Never say that God is just. If He were just, you would be in hell. Rely only on His injustice which is mercy, love and forgiveness.” Surely this explains why “Lord have mercy” appears so often in the Liturgy. Indeed, we strive to become people of mercy, as our Father first extended mercy to us. “Be you therefore perfect, even as your Father in heaven is perfect.” (Mt 5:48)

Added to the Christian’s calling to manifest mercy is the goal to seek out occasions to show mercy, especially under adverse or uncomfortable circumstances, and to strive for more than just expedient answers. As Laurel Rae Matheson recently wrote in Sojourners, “Justice is not just a matter of fairness or equity [but of] creating sustainable solutions for conflict.” In other words, justice should be strongly conciliatory and constructive, rather than “restorative, distributive or punitive.” The end result we seek should be better than any ante bellum condition, hewing much more emphatically toward “the peaceable kingdom.”

As real “just peace” is achieved, we will know it not by the fact that oppressors have become captives or corpses in the cemetery, or that the poor have finally become rich – as satisfying as that kind of compensatory balance might be. Rather, the sword will have been beaten into plowshares.

The peaceable kingdom is described in these amazing words: “The wolf also shall dwell with the lamb, and the leopard shall lie down with the kid; and the calf and the young lion and the fatling together; and a little child shall lead them.” This is a vision that would be laughed out of most negotiating rooms as naively idealistic, yet our faith bids us embrace it. Micah’s prophecy promises that “every one shall rest under his vine, and every one under his fig tree, and there shall be none to alarm them…. All nations shall walk every one in his own way and we will walk in the name of the Lord our God for ever and ever.” (Micah: 4:4-5)

Justice? We might not all call it that all the time. Peace? Surely. Hurry, Christ, bring us Your peace, that we might learn what Your justice truly is!

Alex Patico is secretary of the Orthodox Peace Fellowship in North America.