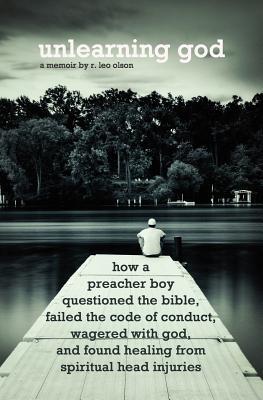

In this excerpt from his memoir, Unlearning God, R. Leo Olson describes his conversion to Orthodoxy from a Protestant fundamentalism as a process of healing from his “spiritual head injuries” and unlearning a problematic understanding of God.

In this excerpt from his memoir, Unlearning God, R. Leo Olson describes his conversion to Orthodoxy from a Protestant fundamentalism as a process of healing from his “spiritual head injuries” and unlearning a problematic understanding of God.

Part of unlearning the conception of God that I had picked up in my fundamentalist Protestant upbringing has been to figure out how to talk about the understanding of God in the Orthodox Church, her different spirituality, and sometimes the ethnocentric life within her. How could I describe what I was experiencing and then tell others, without shredding the spirituality of people from my past? I thought that, rather than try to explain everything, perhaps I should invite them to come and see for themselves. It worked for me.

The first couple of times I invited some of my Protestant friends and family, the service was not entirely in English – a little Greek or Arabic was explainable and acceptable. When a real live bishop was coming to visit, I broke out the first-century letters from St. Ignatius and boasted about how the mystical and true Church manifests itself in a special way when the bishop is present. Some of my seeker friends were excited about this and decided to come and visit.

Of course, the bishop chose to chant almost the entire service in Arabic. I was defeated. I was experiencing a real, incarnational relationship with God and yet could not explain to others why whole parts of the Divine Liturgy were in a different language. I wanted Orthodoxy to be the faith tradition for them, where they could find meaning, healing and encounter God in a real “come-and-see-for-yourself” way. Which language was spoken became a real issue for me as it does for most Protestant seekers and seasoned converts.

I felt like such an American elitist when I demanded the services be entirely in English from my priest. I told him I knew I needed to embrace Orthodox spirituality and worship but could not, would not, if I had to learn Arabic, Russian or Greek. I’m an American, for God’s sake; why do I need to learn a new language? I realized that I was still suffering from a spiritual “head injury” of pride.

I had invited some of my siblings to come to a Christmas Eve service. My brothers and sisters are quite a bit younger than me, and for the most part are products of a mixed Pentecostal/Baptist Christian tradition. Most of them were working through their own “unlearning” of God, but had not taken their faith seriously since they left the practices and faith communities of their own childhood.

They knew I had moved to a different church and suspected that it was a totally different religion. So what better way to show them original Christianity than to invite them to an Orthodox service before a Christmas family party? I mean Christmas is about the birth of Jesus and who He is and why He was born – to save us. I thought that, if I could start with that fundamental truth, this would serve as a foundation for other conversations with them.

We met at my house before the service because I wanted to prepare them, pre-proselytize them, if you will. I had an arsenal of articles, magic Gillquist pamphlets and timelines of church history. I talked for an hour. I was eloquent. I was smooth. I was channeling St. John Chrysostom. [1]

This turned out to be a horrible idea, grossly misjudged by me. I anticipated some of the normal questions about “high church” liturgics, chanting, and icons, and why St. George is slaying a dinosaur like a character from Dungeons and Dragons. I even tackled the “venerational” kissing of icons as not idolatrous. I told them it’s like kissing a picture of Grandma who had Jesus in her heart and thereby reverencing the work of the Holy Spirit, not worshipping Kodak. I could tell I was speaking a foreign language to them and they suspected spiritual trickery of me.

We caravanned to the service. I knew my brother did not want to go to my church because he did not listen to my pre-emptive lecture trying desperately to translate Orthodoxy into his world. But he was forced to attend due to family pressure. We all stood in the back pew of the darkened nave and my brother sat down after one psalm was read, put his hat on and pulled it down low over his eyes. He had checked out seven minutes into the service. The rest of my siblings were wide-eyed, confused and feeling self-conscious that they were under-dressed.

An older gentleman from our parish made his way over to us from the very front and asked my brother to take off his hat. This experience was so horrible for me, I went inside my head and silently recited “Lord have mercy” over and over as fast as I could to get away from my embarrassment.

My brother did take off his hat but did not stand up. He folded his arms with verve and his stubbornness set in. I knew he would endure this Orthodox service once but never again. I recognized this inner passive revolt because we have the same spiritual “head injuries.” I also knew it was hopeless to try and fix this but I leaned down to him anyway and half apologizing and half wanting to punch him in the neck for acting like a jerk, asked, “So pretty different, hey? What do you think so far?”

He looked up at me and asked, “What language is this?” I couldn’t help but laugh and answered, “Um, it’s English. The whole thing has been in English so far.” He rolled his eyes and waited the service out. There was “no room at the inn” for my brother, and I’m pretty sure he wouldn’t have stayed at Hotel Orthodoxy if a room was offered. He has never been back and we have not discussed Orthodoxy or God since.

We had a priest who was born in Syria. He spoke English very well, with a slight accent but definitely bi-lingual, and probably still dreamt in Arabic. Our family loved him even though his stay was brief at our parish. Sometimes during the Divine Liturgy he would read the priestly prayers in Arabic. These prayers are supposed to be silent, according to the red service book in the pew, but most priests say them quietly. It’s a fun “cultural” experience to try and follow along as Arabic is being read by the priest right to left and in the book it’s written left to right in English. However, on this particular Sunday morning, it was more than just the silent prayers of the priest; he was going off in Arabic, almost the whole service. My wife could tell bees were buzzing around my head during the service about this issue.

We had a priest who was born in Syria. He spoke English very well, with a slight accent but definitely bi-lingual, and probably still dreamt in Arabic. Our family loved him even though his stay was brief at our parish. Sometimes during the Divine Liturgy he would read the priestly prayers in Arabic. These prayers are supposed to be silent, according to the red service book in the pew, but most priests say them quietly. It’s a fun “cultural” experience to try and follow along as Arabic is being read by the priest right to left and in the book it’s written left to right in English. However, on this particular Sunday morning, it was more than just the silent prayers of the priest; he was going off in Arabic, almost the whole service. My wife could tell bees were buzzing around my head during the service about this issue.

Soon after joining this ancient and sacred tradition of worship I was able to formulate my own sinful nit-pickings. It happens to everyone. We all have those molehills of which we make mountains from time to time. Arabic dominating the services was mine. I was in desperate need of healing and my whole inner life revolved around learning Orthodox worship, not language lessons. Over half way through the Divine Liturgy our priest was still not using English. I leaned forward and asked a woman in front of us, of Palestinian descent, “What is he saying?”

This was very bad of me. I knew there was no good to come from asking this. As an immigrant she didn’t catch the frustrated American sarcasm of my spiritual head injuries coming out – thank God. But my wife knew full well where my heart was and I could feel her stare in the back of my head.

The woman, leaned back and said, “I don’t know. I can’t understand his accent.” I laughed through my nose and leaned back. My wife looked at me with eyes that said, “I had crossed the line.” I whispered to her, “Even she doesn’t know what the heck language this is.” Her eyes steeled and she replied, “You’ve got a problem and you should watch your own language before you critique the priest.” Afterward, I spoke to the priest about his “over-use” of Arabic in the service. I told him I come here to worship and Arabic is a problem for me. I don’t know what you are saying up there. I could tell he sensed a spiritual head injury in my tone.

“Habibi, (loved one in Arabic) was God praised and glorified today, even if you didn’t know the words?” he asked. He smiled at me without another word of correction needed. I smiled back, full of inner shame that I let my spiritual head injuries lash out like that.

Flashback a few years when my wife and I wanted to visit every parish in town before choosing one to join – that horrible predicament for converts; we had to judge parishes by our own likes and dislikes. We had all but decided to join St. Nicholas, but there was one more parish in town we hadn’t visited. So we did.

Fr. John Estephan, may he rest in peace, was the priest. Fr. John was a highly educated man. He held two doctorates, one in the history of the Middle East and the other in anthropology. He was an ambassador to Lebanon from Mexico, spoke five different languages, of which English was his last and least fluent. He was a priest who had served our city for decades and when he fell asleep in the Lord a couple of years ago, the true fruits of his ministry were seen by all.

As I say, however, English was the last of his languages and he spoke with a thick accent. The Liturgy was great and the choir was grand. Orthodox worship with its ancient ritual and minor toned chanting often transports everyone to a mystical manifestation of the Kingdom of God. I was raptured in spiritual revelry. Then came the homily. Fr. John walked slowly to the podium with many notes and started preaching in English for the most part. He would explain something in Arabic and then in English. It was like he was the speaker and translator for his own sermon. Towards the end of the sermon, he pounded his fist into the podium and said, “If you are not grateful – you are not Christian! How can you say you love someone and not be grateful to them?”

That was all I needed to hear or understand from Fr. John Estephan. We did not choose St. George as a parish because of the “language issue” on our horrible parish evaluation list of “likes and dislikes.” To this day, however, many years later, I have not forgotten the simple truth of those twenty-two words from Fr. John.

St. Paul wrote in 1 Corinthians 13 – the “love chapter” quoted in almost every marriage ceremony – “Though I speak with the tongues of men and of angels, but have not love, I have become sounding brass or a clanging cymbal” (1 Corinthians 13:1). I was the one spiritually injured with the “language issue,” not Orthodoxy. Truth transcends language. Orthodox worship engages all the faculties and senses of a person: touch, taste, smell, feel, hearing, mind, and soul.

My spiritual head injuries deformed my idea of worship because it was hyper-cerebral and still self-centered. If I didn’t understand the language, then it was of no use to me. I demanded Orthodoxy conform to me and my American way of thinking, rather than let it transform me through the universal language of God – love. I had become a “clanging symbol” to those around me by proudly demanding English-only.

The shining light of truth and the healing spiritual medicine of love, known in Orthodoxy, made its way to the “land of the free and the home of the brave” not by religious crusade or a movement of rational enlightenment, but by way of immigrants. Many risked their own lives and forsook all they owned, their loved ones, and all they knew about life to come here to America. They brought with them the most ancient expression of Christianity and worshipped in spirit and in truth the only way they knew how and in the language they spoke. Who was I to demand the terms and conditions of God’s blessings of Orthodox worship? I had a Jonah complex and that didn’t work out so well for Jonah when he didn’t agree with God about the Ninevites. [2]

I don’t know how many times I’ve said, “I wish I knew another language?” Well, I can sample Arabic and Greek and Russian anytime I want. And, unlike my years of studying swear words in French and Spanish classes, I get to learn the very best words in those languages and sing “Lord have mercy” or shout “Christ is risen!” at Easter in multiple languages. To learn the words of praise to our Lord in another language is a great privilege. I am grateful for different languages now. Healing from spiritual head injuries requires the closing of a myopic eye and an openhearted, grateful embrace of someone else and sometimes an entire culture. Orthodoxy is here in America, but it is wrapped in a cultural wrapping paper like a Christmas present.

When I reflect on the language issue now, I remember when my brother didn’t even recognize English in that Christmas Eve service. I spoke so many words to him before he visited. I made biblical arguments about how the Church came before the Bible. I used hollow-point long-range bullets to shoot down praise bands and “pep rally” worship. I said this … Bang! I said that … Fire in the hole! I, I, I – and none of it mattered, because there was no love in my words, no gratefulness. He heard only clanging symbols on that Christmas Eve.

When I am truly grateful for the Lord’s gift of Orthodoxy, instead of demanding He tell me He loves me in English only, my cold Jonah-like heart warms. I begin to truly love other people and all their customs, values and even their languages. I begin to heal. Twenty-two words from Fr. John would have saved me years of frustration and aided my spiritual therapeutic needs; if only I would have had ears to hear then. I would rather say seven true words of faith, hope and love in any language than thousands of my own words that don’t mean anything in the end.

At Pascha (Easter), every patriarch, bishop and priest stands in front of the holy altar of God and proclaims to all, “Christ is risen!” – the only hope of healing for people with spiritual head injuries and salvation for humankind. The people from around the world shout back, “Truly He is risen!” And I am among them. What else is there to know, understand or believe?

Jesus Christ, love incarnate, conquered sin, death and Hades for all people, no matter where they were born or what language they spoke. It is with gratefulness that I stand every Pascha with Orthodox Christians worldwide and mystically with every Christian since the myrrh-bearing women at the tomb discovered it empty, and shout the greatest cosmic archetype mystery of faith, hope and love that the universe has ever heard:

Christ is Risen! Truly He is Risen!

Albanian: Krishti U Ngjall! Vertet U Ngjall!

Aleut: Khristus anahgrecum!Alhecum anahgrecum!

Alutuq: Khris-tusaq ung-uixtuq! Pijiinuq ung-uixtuq!

Amharic: Kristos tenestwal! Bergit tenestwal!

Anglo-Saxon: Crist aras! Crist sodhlice aras!

Arabic: L’Messieh kahm! Hakken kahm!

Armenian: Kristos haryav ee merelotz!Orhnial eh

harootyunuh kristosee!

Aroman: Hristolu unghia! Daleehira unghia!

Athabascan: Xristosi banuytashtch’ey!Gheli banuytashtch’ey!

Bulgarian: Hristos voskrese! Vo istina voskrese!

Byelorussian: Khristos uvoskros!Zaprowdu uvoskros!

Chinese: Helisituosi fuhuole!Queshi fuhuole!

(Cantonese): Gaydolk folkwoot leew! Ta koksut folkwoot leew!

(Mandarin): Ji-du fu-huo-le!Zhen-de Ta fu-huo-le!

Coptic: Pi-ekhristos Aftonf! Khen oomethmi Aftonf!

Czech: Kristus vstal a mrtvych!Opravdi vstoupil!

Danish: Kristus er opstanden!Kristus er opstanden!

Dutch: Christus is opgestaan! Ja, hij is waarlijk opgestaan!

Eritrean-Tigre: Christos tensiou!Bahake tensiou!

Esperanto: Kristo levigis! Vere levigis!

Estonian: Kristus on oolestoosunt!Toayestee on oolestoosunt!

Ethiopian: Christos t’ensah em’ muhtan!Exai’ ab-her eokala!

Finnish: Kristus nousi kuolleista!Totistesti nousi!

French: Le Christ est réssuscité! En verite il est réssuscité!

Gaelic: Kriost eirgim! Eirgim!

Georgian: Kriste ahzdkhah!Chezdmaridet!

German: Christus ist erstanden! Er ist wahrhaftig erstanden!

Greek: Christos anesti! Alithos anesti!

Hawaiian: Ua ala hou `o Kristo! Ua ala `I `o no `oia!

Hebrew: Ha Masheeha houh kam! A ken kam! (or Be emet quam!)

Icelandic: Kristur er upprisinn! Hann er vissulega upprisinn!

Indonesian: Kristus telah bangkit!Benar dia telah bangkit!

Italian: Cristo e’ risorto! Veramente e’ risorto!

Japanese: Harisutosu siochatsu!Makoto-ni siochatsu!

Javanese: Kristus sampun wungu!Saesto panjene ganipun sampun wungu!

Korean: Kristo gesso! Buhar ha sho nay!

Latin: Christus resurrexit! Vere resurrexit!

Latvian: Kristus ir augsham sales!Teyasham ir augsham sales vinsch!

Lugandan: Kristo ajukkide! Amajim ajukkide!Malayalam

(Indian): Christu uyirthezhunnettu!Theerchayayum uyirthezhunnettu!

Nigerian: Jesu Kristi ebiliwo! Eziao’ biliwo!

Norwegian: Kristus er oppstanden! Han er sannelig oppstanden!

Polish: Khristus zmartvikstau!Zaiste zmartvikstau!

Portugese: Cristo ressuscitou! Em verdade ressuscitou!

Romanian: Hristos a inviat!Adevarat a inviat!

Russian: Khristos voskrese!Voistinu voskrese!

Sanskrit: Kristo’pastitaha! Satvam upastitaha!

Serbian: Cristos vaskres! Vaistinu vaskres!

Slovak: Kristus vstal zmr’tvych!Skutoc ne vstal!

Spanish: Cristos ha resucitado! En verdad ha resucitado!

Swahili: Kristo amefufukka! Kweli Amefufukka!

Swedish: Christus ar uppstanden!Han ar verkligen uppstanden!

Syriac: M’shee ho dkom! Ha koo qam!

Tlingit: Xristos Kuxwoo-digoot!Xegaa-kux Kuxwoo-digoot!

Turkish: Hristos diril-di! Hakikaten diril-di!

Ugandan: Kristo ajukkide! Kweli ajukkide!

Ukranian: Khristos voskres!Voistinu voskres!

Welsh: Atgyfododd Crist!Atgyfododd in wir!

Yupik: Xristusaq Unguixtuq!Iluumun Ung-uixtuq!

Zulu: Ukristu uvukile! Uvukile kuphela!

Author’s notes:

[1] St. John Chrysostom (347-407 A.D.) was known for his eloquence in preaching and public speaking, and assembling the Divine Liturgy of St. John Chrysostom. He was given the Greek epithet chrysostomos, meaning “golden-mouthed.”

[2] Jonah was the reluctant prophet of God. He did not want to share God’s message with a foreign people. After being swallowed by a fish and vomited on a beach, he angrily preached God’s message then went on a hill to watch the Ninevites burn. They repented. Jonah was consumed with anger at God’s mercy on a foreign people. He was even annoyed with God about the plant that shaded him, but then died, no longer providing him shade while he hoped for Nineveh’s destruction (Jonah 4).