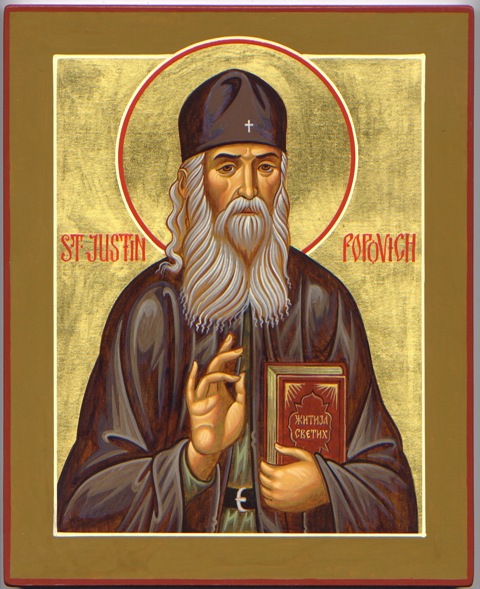

Today the Serbian Orthodox Church celebrates the memory of St. Justin of Ćelije, who was glorified in 2010. (Although he reposed on the Feast of the Annunciation, he is commemorated on the feast day of his patron saint, St. Justin the Philosopher.) In his honor we offer the following study of his life and works, originally published in Russian in 1984.

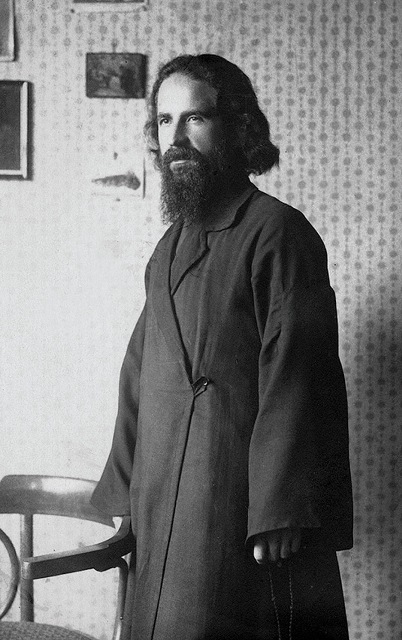

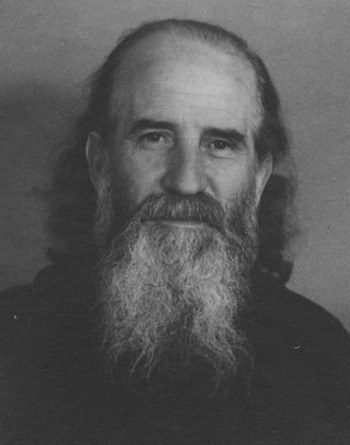

The name of Archimandrite Justin (Popović +1979), doctor of theology, is held in great renown in the Local Orthodox Churches.

The name of Archimandrite Justin (Popović +1979), doctor of theology, is held in great renown in the Local Orthodox Churches.

Archimandrite Justin was born on April 7, 1894, on the Feast of the Annunciation of the Most Holy Theotokos, in the ancient Serbian city of Vranje to the pious family of a priest, which had given the Serbian Church seven generations of clergy. In Baptism he was given the name Blagoje, in honor of the Feast of the Annunciation.

From 1905 to 1914, Blagoje Popović studied at the Seminary of St. Sava of Serbia in Belgrade. During his years of study, the young Blagoje was especially interested in questions of contemporary literature and philosophy. He paid the greatest attention to the works of Dostoevsky, about whom he later wrote two studies: The Philosophy and Religion of F. M. Dostoevsky and Dostoevsky on Europe and Slavism.

The works of the Holy Fathers had a decisive influence on the formation of Archimandrite Justin’s spiritual character. The Holy Fathers were, and remained to the end of his life, his irreplaceable teachers and instructors. He was wholly guided by their teachings. Archimandrite Justin especially loved St. John Chrysostom, to whom he prayed ceaselessly with childlike sincerity: “I feel St. John Chrysostom’s particular, merciful closeness towards me, a sinner,” he wrote, “My soul ascends to him in prayer: enlighten me by thy prayers… grant me to struggle with your struggle…”

In 1916, Blagoje Popović accepted monastic tonsure with the name Justin, in honor of Hieromartyr Justin the Philosopher (+166; celebrated on June 1). Indeed, like him, Archimandrite Justin was a genuine philosopher who internalized the truth of Christianity. He placed humble-mindedness at the foundation of his theology, following the example of St. John Chrysostom, who is known for these remarkable words: “The foundation of our Christian philosophy is humble-mindedness, for without it truth is blind.” This is why Fr. Justin, in his contemplation of God, does not speak about Christ as an ordinary person (or an “historical personage”), but rather as the God-Man, the Savior of the world. Fr. Justin felt that the only authentic theologizing of Christ in the Holy Spirit is the contemplation of God in which mind and heart (thought and feeling) are united in prayer, passing into contemplation and Divine vision. He often said: “Any of my thoughts that arises without being converted into prayer is oppressive.”

Shortly after his tonsure, with the blessing of the Serbian Metropolitan Dimitrije (later His Holiness, the Patriarch of Serbia), Fr. Justin went to Petersburg, where he enrolled in the theological academy. During his time studying in the academy, Fr. Justin got to know Orthodox Russia well and to love it deeply. Here he acquired extensive theological knowledge and grew spiritually, becoming acquainted with Russian holy things and the works of the saints. From this time, and throughout his life, Fr. Justin deeply loved St. Sergius of Radonezh and other Russian saints; he acquired a particularly close spiritual and prayerful closeness to St. Seraphim of Sarov. Even then, Fr. Justin understood that the soul of the people, its spirit, is hidden in the great deeds of the saints, for true Orthodoxy is the acquisition of the Holy Spirit.

In June 1916, Fr. Justin went to England, where he enrolled in the University of Oxford. He studied there until 1919, when he returned to his homeland. In the same year he went to Athens, where he worked until 1921 on his doctoral dissertation, “The Problem of Personhood and Knowledge According to St. Macarius of Egypt,” which he successfully defended in 1926 in Athens. (Part of the dissertation was later published in the journal Theology, Righteousness, and Life. Athens, 1962, pp. 153-175). Throughout these years, Fr. Justin’s prayerful struggles were strengthened, as demonstrated by his spiritual meditations: “How many years must one add the fragrant leaven of Heaven into the dough of one’s essence? How many years must one spend remaking oneself through the evangelical virtues? From the cave of my body I behold Thee, O Lord, and continue to gaze, but cannot quite see. But I know, I feel, and I know that Thou are the only Architect, O Lord, Who can build the eternal house of my soul. The builders are prayer, tears, fasting, love, humility, meekness, patience, hope, compassion…”

In June 1916, Fr. Justin went to England, where he enrolled in the University of Oxford. He studied there until 1919, when he returned to his homeland. In the same year he went to Athens, where he worked until 1921 on his doctoral dissertation, “The Problem of Personhood and Knowledge According to St. Macarius of Egypt,” which he successfully defended in 1926 in Athens. (Part of the dissertation was later published in the journal Theology, Righteousness, and Life. Athens, 1962, pp. 153-175). Throughout these years, Fr. Justin’s prayerful struggles were strengthened, as demonstrated by his spiritual meditations: “How many years must one add the fragrant leaven of Heaven into the dough of one’s essence? How many years must one spend remaking oneself through the evangelical virtues? From the cave of my body I behold Thee, O Lord, and continue to gaze, but cannot quite see. But I know, I feel, and I know that Thou are the only Architect, O Lord, Who can build the eternal house of my soul. The builders are prayer, tears, fasting, love, humility, meekness, patience, hope, compassion…”

Beginning in 1921, Fr. Justin taught New Testament, dogmatic theology, and patrology at the seminary in Sremska Karlovci. He was ordained a hieromonk in 1922, from which point he became a spiritual father to many of his flock.

In 1930, the Holy Synod of the Serbian Orthodox Church appointed Fr. Justin to be the assistant of Bishop Josif of Bitola. The joint task of Vladyka Josif and his assistant was the organization of Orthodox parishes in Czechoslovakia, especially in the Prešov region in so-called Carpatho-Russia, where Uniates were beginning to return to the bosom of Orthodoxy.

Fr. Justin devoted a great deal energy to this truly difficult but God-pleasing labor. Slovak Christians themselves sought out help. For that reason, Bishop Josif asked the Holy Synod to consecrate Fr. Justin as bishop of the newly-restored Mukachevo Diocese in Transcarpathia. But Fr. Justin refused to accept the episcopal rank. His letter to Vladyka Josif testifies to this: “I ask Your Grace to pardon me and forgive me for doing this. I write this by the irresistible conviction of my conscience… I have refused before and I refuse again to accept the rank of bishop. My refusal is not the result of a passing mood… I have looked long and hard at myself, based on the Gospel. I have judged myself according to the Gospel and arrived at this invariable conclusion: I cannot accept the rank of bishop under any circumstances. For I know myself very well: it is very difficult to keep my own soul within the boundaries of Christ’s goodness, not to mention the souls of hundreds of thousands of other people, and to answer for them before God.”

In 1932, Fr. Justin returned from Czechoslovakia and began work on the first volume of his Dogmatics, which was published that same year. He then became a professor at the Theological Seminary in Sremska Karlovci. Two years later the Holy Synod appointed him lecturer in the Theological Faculty at the University of Belgrade.

In 1932, Fr. Justin returned from Czechoslovakia and began work on the first volume of his Dogmatics, which was published that same year. He then became a professor at the Theological Seminary in Sremska Karlovci. Two years later the Holy Synod appointed him lecturer in the Theological Faculty at the University of Belgrade.

In 1935, Fr. Justin published the second volume of his Dogmatics, in which he sets forth the Orthodox teaching on the God-Man and His work (Christology and soteriology).

In the same years, together with other prominent members of Serbian spiritual culture, Fr. Justin participated in the founding of the Serbian Philosophical Society.

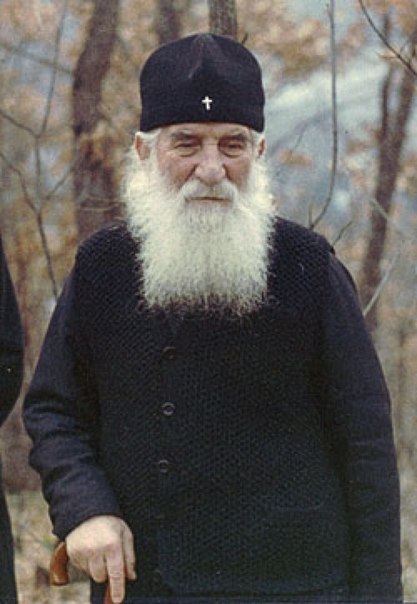

In 1948, Fr. Justin was appointed spiritual father of the Ćelije convent. He stayed here until the end of his life, devoting his time to prayer, Divine contemplation, scholarly theological work, and translating.

Quite a lot has been written in various Orthodox journals about Fr. Justin’s contribution to contemporary Orthodox theology. A special issue of the Greek ecclesiastical journal Paradosis (Tradition) for 1979 was dedicated to him.

The author of one article dedicated to his life and work, published in connection with Fr. Justin’s repose, wrote: “It would be no exaggeration to characterize him as one of the most outstanding contemporary Fathers of Orthodox theology.”

Fr. Justin’s legacy as an author is voluminous: three volumes of Dogmatics, twelve volumes of The Lives of Saints, various theological works, and numerous epistles and letters. Fr. Justin’s works, which are full of theological depths and exalted poetry, embodied his inner spiritual experience.

To penetrate the spirit of Archimandrite Justin’s theologizing, the two most valuable works are his Dogmatics and The Lives of Saints.

In the introduction to the first volume of his Dogmatics, Fr. Justin writes: “Moved from non-existence to All-existence, man – dressed in the wondrous forms of matter and spirit – journeys through the wondrous mysteries of God. The further he is from non-being and the closer to All-being, the more he hungers for immortality and sinlessness and the more he thirsts for the inaccessible and eternal. But there is a tyrannical pull towards non-existence, while sin and death greedily rob the soul. All the wisdom of life is contained in overcoming non-being in and around us and immersing ourselves entirely in All-being. The Holy Spirit teaches this wisdom, for He is wisdom and knowledge – grace-filled wisdom and grace-filled knowledge about the nature of being. The center of this wisdom is knowledge of the Divine and the human, of the invisible and the visible. Divine contemplation of the Holy Spirit is at the same time a morally creative power, through which the process of man imitating God on the path of ascetic, grace-filled perfection multiplies Divine knowledge of God and the world in man. Being quickened by the Holy Spirit is the only art that can sculpt a variegated and very complex human being into a person in the likeness of God, in the image of Christ.

“Knowledge of God in the Holy Spirit is, in this way, that truth about God, the world, and man that the Orthodox Church calls dogmas of faith. Therefore dogmatics is a science of the eternal truths of God that are revealed to people that they might put them into practice in their lives, thereby attaining the eternal goal of our existence, of our martyric journey from non-being to All-being…”

The living embodiments of these Divinely-revealed truths, Fr. Justin believed, are the saints, who are the bearers of these truths as well as their preachers and confessors.

The Orthodox dogmatist should turn with all his works to the saints, to learn from them and to be in prayerful communion with them, in fasting and spiritual wakefulness. Thus, the Orthodox dogmatist’s work is the ascetic struggle of sobriety of mind.

In the introduction to his Exact Exposition of the Orthodox Faith, St. John of Damascus once and for all consolidated the guiding principle for establishing a dogmatic system: “I will not say anything of myself, but will explain briefly what God’s wise men have said.” Citing these words of the great saint, Fr. Justin testifies: “I, in my nothingness and misery, can hardly dare say that I have in fact kept to his principle. If anything in my work is good, evangelical, and Orthodox, then all that belongs to the Holy Fathers, and everything that is opposed thereto is mine, and mine alone.”

Fr. Justin says that through the Incarnation of the Son of God, Divine Truths have become more accessible to man. This means that Christ is necessarily repeated in every Christian, for every Christian is an organic part of Christ’s Church, which is His Divine-human Body.

Fr. Justin saw the path to immortality in the organic unity of man with the Person of the God-Man Christ, with His Body, with the Church. “I know and I feel,” he wrote, “that only in Him and with Him am I an eternal self, a divine eternal self. But without this I do not need myself.”

The goal of the Church’s ministry is that all believers would unite organically and personally with the Person of Christ, so that their self-perception would become Christ-perception and their self-consciousness would become Christ-consciousness, so that their entire life would be the life of Christ, and so that they no would longer live, but Christ in them (cf. Galatians 2: 20).

Finding oneself means finding the God-Man Christ in oneself, but He abides only in His Church, which is His living incarnation. It is a Divine-human eternity, incarnate within the boundaries of time and space. It is in the world, but not of the world (cf. John 18:36). Therefore, in the Church the Person of the God-Man Christ is the only guide leading man though mortality and temporality into immortality and eternity.

God became Man, while remaining God, so that as God He could give human nature the Divine power that would lead man to the most intimate Divine-human unity with God. His Divine power works unceasingly in His Divine-human body, the Church, uniting people with God through the grace-filled and holy life. For the Church cannot be anything other than a wondrous and miracle-working Divine-human organism, in which – through the interaction of God’s grace and human freedom – it would form immortality and deify everything human except sin. In the Divine-human organism of the Church every believer is like a living cell becoming an integral part of that organism and living by its Divine-human power.

By calling the Church the Body of Christ, the Holy Apostle Paul establishes a link between its essence and the mystery of God’s Incarnation, showing that the living and unchangeable foundation of the Church resides in the fact that that the Word became flesh (John 1:14). This is the Church’s foundational truth. The Church is primarily a Divine-human organism and only subsequently a human community.

By calling the Church the Body of Christ, the Holy Apostle Paul establishes a link between its essence and the mystery of God’s Incarnation, showing that the living and unchangeable foundation of the Church resides in the fact that that the Word became flesh (John 1:14). This is the Church’s foundational truth. The Church is primarily a Divine-human organism and only subsequently a human community.

The nature of the Church is Divine-human, from which follows its Divine-human activity in the world: everything Divine becomes incarnate in man and in humanity. Therefore, the Church’s mission, its very nature, is to realize Divine-human, spiritual values in the human world.

As Fr. Justin emphasized, by confessing the God-Man, the Church also confesses man in his authentic and God-created unity. For without the God-Man, there can be no true man.

The ontology of human personhood is its Divine image. In the Divine image, man is given all the Divine power needed to achieve eternal perfection: “My infinity draws me to Thee, O Infinite God!”

Man’s value, Fr. Justin testifies, is determined by his inner world. In its unfathomable depths, the inner world is in contact with Absolute Reality, of Which man is the bearer. By maintaining such a connection, that is, by absorbing in themselves the eternity of the spiritual kingdom, Christians by virtue of their continuous spiritual growth become infinite, although not without beginning. Indeed, who can explore the metaphysical depths of man? For who among men knoweth the things of a man, except the spirit of the man that is in him (1 Corinthians 2:11). He who earnestly observes the material and spiritual realities of the universe cannot but feel the presence of an infinite mystery in all phenomena. The human spirit persistently strives to comprehend the mysterious. The constant movement of the human spirit in that direction is a second, supernatural component of him as person. Bearing this natural component in mind, Fr. Justin resolves the fundamental question of anthropology in this manner: “We can conclude that man is man precisely because he is the bearer of an individual supernatural gift that manifests itself in perfection, creativity, and mental activity.” The entire human spirit longs for eternity: through consciousness and through the senses, through will and through all life – which means that it longs for immortality. Thus, Fr. Justin believes that the human aspiration to infinity, to immortality, belongs to the very essence of the human spirit.

Created in God’s image, man is full of spiritual yearning, since the Divine image is the principle component of man’s essence. This yearning of the Divinely-imaged soul towards its Archetype is natural.

By giving man the commandment: Be ye perfect, as your Father in heaven is perfect (Mathew 5:48), the Lord Jesus Christ indicates the grace-filled possibility of realizing the Divine-image in human nature, since He would not have commanded the impossible.

The image of God in man’s nature, Fr. Justin remarks, has an ontological and a teleological meaning: ontological, because the essence of the human being is found therein; and teleological, because it indicates the goal of life, which is unity with God.

But by inclining his free will toward sin, man – rather than becoming a communicant of Divine life by virtue of the Divine image in his soul – distanced himself from the Divine. He retreated into himself and began to live without the supernatural guide inherent to his nature. That was his first act of opposing the Divinely-imaged composition of his own essence. From that time, man has rendered himself godless by forcing God out of himself and into a supra-human, supra-mundane transcendence. He found himself facing a gaping abyss separating him from God. The human essence suffered a catastrophe that disrupted the God-created nature of man and shifted its center. Consequently, man lost the ability to understand himself and the world around him.

Man’s love of sin gave the devil power over him, creating the danger of the formation of a “devil-man.” It was at this point that the God-Man came into the world to save man from sin, evil, devil, and eternal death.

By His death on the Cross, our Lord Jesus Christ gave man the opportunity to return to the Divine image, to move from sin to Light and Truth, and from death to Life.

When the God-Man Jesus Christ raised Himself on the Cross, He simultaneously raised man to the first level of Heaven, on which He reconciled the two worlds, the Heavenly and the earthly, uniting Heaven and earth. At the top of this ladder is He Himself: the King of Glory, the Way, Truth, and Life. Behold, O man, how many opportunities have been given you to grow upwards! From the bottom of the abyss to the height of heaven, and higher than any heavens!

The ability to think is Divine in nature and of heavenly origin. It was given to man in order to join him with Heaven, God, and eternity.

But pride, that powerful instrument of the enemy of salvation, caused human thought to separate itself from God and caused man to imagine himself infallible.

Man’s true spiritual nature consists exclusively in victory over death, in the ultimate transfiguration of soul and body, and in liberation from sin and evil – those sources of death. Certainty of immortality comes through knowledge of God, which does not tolerate the sin that engenders death.

Beginning in 1972, Archimandrite Justin began publication of his twelve-volume work called The Lives of Saints, which he had compiled long before. The publication of this very significant work was completed by the end of 1978. Soon after the publication of The Lives of Saints, hagiology was introduced as a permanent course in the curricula of theological seminaries.

If Fr. Justin’s Dogmatics was the fruit of his predominantly ecclesio-academic research, The Lives of Saints reveals the spiritual experience of a man filled with Christ to his very depths. The Lives of Saints shows us the mysterious path to Christ that all the ascetics had followed. The author of The Lives of Saints, being an ascetic himself, understands the tears of ascetics; being a martyr for faith, he understands the pain of martyrs; being a monk, he understands the monastic experience of attaining the Divine; and being a modern Orthodox theologian, he understands the theology of the Fathers and teachers of the Church.

Fr. Justin began his translation into Serbian, and systematic work on, the lives of saints of the Orthodox Church after World War II. Fr. Justin comments on his reasons for writing that “simple” – in comparison to his dogmatic works – book: “The lives of saints are, as a matter of fact, dogmatics incarnate, because in them all the eternal and holy dogmatic truths come to life in all their life-giving and substantive force.”

The lives of saints confirm in the most visible fashion that dogmas are not only ontological truths in and of themselves, but that every dogma is a source of Eternal Life and holy spirituality, in accordance with the words of the Savior: the words that I speak unto you, they are spirit, and they are life (John 6:63). For the Lord’s every word gives man a saving, sanctifying force that fills him with joy, enlivening and transforming him. The lives of saints contain the entirety of Orthodox ethics in all their magnificence and irresistible power. The lives of saints are “the only pedagogy of Orthodoxy” and “an Orthodox encyclopedia of sorts.” Fr. Justin views the lives of saints as a continuation of the Acts of the Apostles, which tell of and confirm the spread of Christianity. The lives of saints are likewise the Gospel, life, truth, love, faith, eternity, and power of the Lord – for Jesus Christ is the same yesterday, and today, and forever (Hebrews 13:8).

In any age, the Lord grants the same grace and performs the same Divine works for all who believe in Him. As Fr. Justin remarks, saints “are the people in whom the holy Divine-human life of Christ is continued from generation to generation, unto the end of the ages.” They all constitute the Body of Christ –the Church – and are inseparably united with Christ and one another. The river of immortal Divine life begins with the God-Man Christ, through Whom Christians come to Eternal life. The lives of saints are of great significance, because “we cannot reach” the holy and Eternal life “individually, but we can do it with all the saints, with their help and under their guidance, through the Holy Mysteries and through good works in the Church.” It was this significance of the saints – and, consequently, the importance of their lives for our salvation in the Church – that compelled Fr. Justin to write the first complete Orthodox Synaxarion in Serbian, that is, a compilation of the lives of saints.

Important sources for Fr. Justin were the Synaxarion of St. Nicodemus the Athonite, The Lives of Saints (Menologion) of St. Dimitry of Rostov, original Greek manuscripts from various critical editions, the Synaxarion of the Church of Constantinople, and many other patristic and theological works.

Fr. Justin ends his collection of lives with a historic overview of attempts to write the lives of saints in early Christianity, starting from the Acts of the Apostles, in which the Evangelist Luke first described “the labors and sufferings of the first disciples of our Savior and of His successors.” Following this overview, Father Justin analyzes the narratives about the holy ascetics published as Paterikons, Gerontikons, and Limonarions, as well as collections of lives of saints from the Byzantine and post-Byzantine periods, and so on, up to the modern critical editions of ancient hagiographic manuscripts. Those latter publications are characterized by the spirit of rationalistic criticism that, according to Fr. Justin’s words, places “the position of their authors against the lives of saints.”

In accordance with Orthodox tradition, Fr. Justin allocates the rich hagiographic material of the liturgical year according to the indiction. Each volume (for September, October, etc.) contains the lives of saints commemorated in the given month. Each life of a saint commemorated on the same day is given a special chapter. In addition, wherever space permits, a photograph is included of an Orthodox church or monastery named after the saint. The entire twelve-volume edition contains images of more than two hundred Orthodox churches that vividly demonstrate the characteristic features of the church architecture of Orthodox peoples from Alaska to Korea and Japan, and from Africa to India. The life of each saint is normally accompanied by photographs of ancient and modern icons of the saint. At the end of each volume there is an alphabetic index of the names of the saints whose lives are included in that volume.

Fr. Justin was hoping to publish a thirteenth and final volume dedicated to the Paschal cycle, that is, to the Lenten Triodion and Pentecostarion.

Simultaneously with the publication of The Lives of Saints, the lives of the most revered Serbian saints were published in separate editions. The publication of The Lives of Saints aroused great interest within the Serbian church community, especially among teachers of Serbian Church history in theological schools. These books are being currently used as textbooks for students in these schools. Abundant information on church history, hagiography, patristics, dogmatics – as well as canonical, pastoral, liturgical, and homiletic materials – is collected in the 8,300 pages of The Lives of Saints. Archimandrite Justin managed to make the Synaxarion not only a narrative text and an academic work, but also a work expressing deep theological authority. The edition soon became a bibliographic rarity.

The value of Fr. Justin’s hagiological work is priceless for the Serbian Church. The lives of the Serbian saints contain the history of the Serbian Church and the Serbian state. The holy Nemanjić dynasty – beginning with its holy forefather Simeon, founder of the Hilandar monastery on Athos, and his son St. Sava, the first Archbishop of Serbia, and ending with its final descendant, the Martyr Uroš – united crown and Cross, uniting the ecclesiastical and state history of the Serbs. Of invaluable help in theological education are the lives of other, non-Serbian saints, as well as the many quotations from the theological works of the Fathers, teachers, and holy ascetics of the Church published in this first complete Serbian Synaxarion.

His Lives are of great importance for all of Orthodoxy. By God’s dispensation, Fr. Justin studied in England, where he came into contact with the non-Orthodox world and its way of thinking; as well as in Russia, where he grasped the depth of Russian Orthodox spirituality; and in Athens, where – as he himself said – he fell in love with the patristic tradition. In Athens he met the outstanding Greek theologians of his time, Professors Balan and Diovuniotis, and studied with John Karmiris, the famous professor of dogmatics and future academician. Here he received the opportunity to study the Byzantine manuscripts that later became part of his Synaxarion. This knowledge of many Orthodox peoples and traditions allowed Fr. Justin to create a work that can be truly considered the shared property of all Orthodox people due to its scale and importance.

With the passage of time, this work by Fr. Justin will play an increasingly important role in introducing Orthodoxy and its spiritual values to the non-Orthodox and non-Christians. This original ecclesio-academic work is a model Orthodox Synaxarion. Henceforward it will be impossible to compile a Synaxarion without knowledge of Archimandrite Justin’s work.

Among the published works of Archimandrite Justin, apart from those already mentioned, we will note the following: The Epistemology of St. Isaac the Syrian, Man and the God-Man: Studies in Orthodox Theology, Foundational Theology, The Theology of St. Sava as Philosophy of Life, The Life of St. Sava and St. Simeon, The Orthodox Church and Ecumenism, and On the Forthcoming Holy and Great Council of the Orthodox Church.

Father Justin’s theological works, in the words of academician John Karmiris, represent the Serbian Church’s pinnacle of spiritual self-expression (preface to the Greek edition of the book Man and the God-Man. Athens, 1st ed. 1969. 2nd ed. 1974. p. 7).

Archimandrite Justin also left behind some unpublished works: Through Life With the Apostle Paul (a multi-volume commentary on the Apostle Paul’s epistles); Commentary on the Catholic Epistles of the Holy Apostle John the Theologian; Commentary on the Gospels according to Matthew and John; the thirteenth volume of The Lives of Saints (on The Lenten Triodion and Pentecostarion; akathists to many saints; and numerous other theological and liturgical texts. Archimandrite Justin, humble clergyman and prominent theologian, belongs not only to the Serbian Church, but to the entire Orthodox world.

As Metropolitan Irenaeos of Crete said of him: “He was a grace-filled gift given by the Lord to the Holy Orthodox Church.”