There is likely not a single history textbook that speaks of Blessed Xenia of Petersburg, whose memory we celebrate today. Yet every history textbook unfailingly contains something about Napoleon and his deeds. These two people lived at approximately the same time: at the turn of the nineteenth century. Are their contributions to history indeed completely incommensurate?

Napoleon’s deeds are well-known: hundreds of thousands of victims (some of whom are buried here, in Sretensky Monastery); devastated and plundered churches – not just in Russia, but also in Venice, for instance, and throughout all of Europe; and the ruined lives of many. In his time Napoleon also wielded tremendous spiritual influence, as evidenced by the works of Tolstoy and Dostoevsky, for example. Raskolnikov, tormented by doubts – “Am I a trembling creature, or have I the right?” – hacked away at the old woman with an axe, one might say, with Napoleon’s name on his lips…

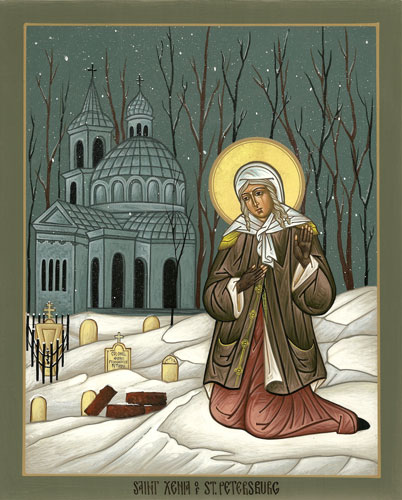

The life of Blessed Xenia is likewise well-known to us: at the age of twenty-six, still quite a young woman, she was suddenly widowed. She took upon herself the ascetic struggle of foolishness for Christ’s sake, abandoning her home, wandering about in her invariable red jacket and green skirt, or green jacket and red skirt, being subjected to constant ridicule and insult, while remaining in unceasing prayer. For her years-long ascetic struggle, incomprehensible to the world, Blessed Xenia received from God the grace to help people quickly and effectively; her role in the fates of thousands had been manifest clearly and triumphantly.

Her special gift was in arranging many people’s family lives. Once, while visiting the Golubev family, Blessed Xenia announced to their seventeen-year-old daughter: “Here you are making coffee while your husband is burying his wife at Okhta. Run there quickly!” The girl, confused, did not know how to react to such strange words, but Blessed Xenia compelled her – literally with a stick – to go to the Okhta cemetery in St. Petersburg. There, burying his young wife who had died in childbirth, stood a doctor who was weeping inconsolably and finally lost consciousness. The Golubevs tried to comfort him as best as they could. This is how they became acquainted. The acquaintance continued after a certain period of time and, one year later, the doctor proposed to the Golubevs’ daughter; their marriage was as happy as could be. Similar cases of how Blessed Xenia helped in arranging families are innumerable: she truly became a begetter of human lives.

Napoleon is buried in central Paris, in the chapel dome of Les Invalides, to which tourists eagerly come to peek at his sarcophagus of red porphyry mounted on a pedestal of green granite. No one comes to pray or to ask him for something; for our contemporaries, Napoleon is just a museum piece, a part of the ossified past. His influence today is negligible: at best, it can provide hackneyed material for films or for pseudo-historical exercises for budding graphomaniacs.

Blessed Xenia’s grave has been, for more than two hundred years already, a source of healing, efficacious help in difficult circumstances, and resolution of intractable problems. For example, Blessed Xenia appeared to a man suffering from alcoholism, telling him sternly: “Give up drinking! The tears of your mother and wife have flooded my grave!” Need I mention that this man never touched the bottle again?

Every day thousands of people gathered (and continue to gather) at Blessed Xenia’s grave, asking her help and leaving notes with cries for help; these notes have always covered the saint’s chapel like a garland. Hundreds, thousands, and millions of notes have called upon her name. But has a single such note ever been left at Napoleon’s grave of red porphyry on a green pedestal?

In contemporary historical studies, the term “social history” is becoming increasingly widespread. This is a very promising direction, because it draws attention to the lives of simple people, to the meaning of “small deeds” in the life of society, and to the decisive roles of ordinary people in the historical process.

One would be wrong to think that history is made by the mighty of this world or upon the peaks of political power; history is not at all what we are shown on television. Real history takes place in the human heart: if someone cleanses himself through prayer, repentance, humility, and patience in affliction, then his role in his own life, and thus in the lives of those around him – and thus in all human history – increases immeasurably.

Blessed Xenia did not head a government, did not gather an army of thousands, and did not lead it on campaigns of conquest; she simply prayed, fasted, humbled her soul, and patiently endured all offense. Yet her influence on human history has been immeasurably greater than that of any Napoleon. Even if the history textbooks do not talk about this…

Christ, however, speaks to us of this in the Gospel: For what shall it profit a man, if he shall gain the whole world, and lose his own soul?[Mark 8:36]. Having in mind the example of Napoleon and Blessed Xenia, these words become all the more convincing.

History is made neither in the Kremlin nor in the White House, neither in Brussels nor Strasbourg, but rather here and now in our hearts, if they are open to God and to people. Amen.

Translated from the Russian.