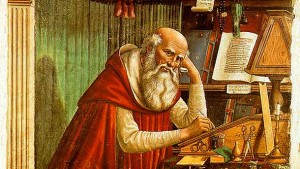

Fr John Nankivell answers the question of why Christians today should read the great Fathers of the Fourth Century such as SS John Chrysostom, Basil and Gregory of Nyssa. Giving an overview of their lives and writings, he looks at what we can learn from their approaches and how we can apply this to our own lives.

Based on a talk given on 26 January 2011 at St Catherine’s Greek Orthodox Church in Barnet on St Gregory the Theologian

The first part of this article will attempt to give an idea of the diversity of the writings of some of the Fathers of the fourth century; the second will touch on the qualities that characterise their life and work; and the third will say something of ‘their significance for us today.’

A. Extracts from their writings

Christ is born, glorify Him

Christ from heaven, go to meet Him

Christ on earth, be ye lifted up

Let the heavens rejoice and the earth be glad

Because of Him who is of heaven and is now on earth

Old things have passed away, behold all things are becoming new

The letter gives way and the spirit comes to the fore

He who was without a mother, being begotten of the Father before the ages

Now becomes without a father, being born of the virgin [1]

When we hear these extracts from a sermon of St Gregory the Theologian, we feel like singing them. And this is precisely what we do every year in the Christmas Matins, and in fact at every matins from the feast of the Entry of the Theotokos on 21st November:

Χριστός γεννάται δοξάσατε

Χριστός εξ ουρανόυ απαντήσετε

Χριστός επι γής υψώθητε…….

The immediacy, the depth, the vigour and the lucid eloquence of his words mean that they move effortlessly into the liturgical poetry of the Church.

And this is no accident. All the Fathers we are considering had enjoyed an education at the highest level in the age called by scholars ‘the Second Sophistic’, second only to the golden times of classical Greece. All had sat at the feet of the leading teachers of their day: St Basil & his friend St Gregory in Athens; St John Chrysostom in Antioch with Libanius, renowned throughout the world then and by posterity as the most eloquent, learned and rigorous of teachers; and St Ambrose from the leading exponents of the classical curriculum in the Latin west. They were all at home with the classical poets, philosophers, orators and play-writes, the eloquence of whose work was ever before them as an inspiration and guide.

They were aware of the responsibility that their privileged education and exceptional gifts laid upon them. Their sermons and writing were for a particular place and time: but they created works that could act as models for any bishop or preacher, not only of their own day, but for subsequent generations. Five hundred years later in Thessaloniki, for example, we find ‘Constantine the Philosopher’ – St Cyril, whose name was taken to describe the alphabet ‘cyrillic’ which he devised in order to take the Gospel to the Slavs – learning the writings of St Gregory the Theologian, and addressing him: ‘Oh Gregory, man in body and angel in spirit … be my teacher and my enlightener’.

In his old age, St Gregory ‘edited a selection of his letters as examples of epistolary art, and a collection of orations that cover all the major needs of preaching for a hierarch: encomia, consolations, doctrinal instructions, missionary apologetic, political intervention, and invective.’.[2] Their writings have inspired, informed, instructed and encouraged Christians in every generation from their own until the present. Take this little section from a letter of St Basil written to console a father on the death of his son:

His life is not destroyed: it is changed for the better.

He whom we love is not hidden in the ground: he is received into heaven

The time of our separation is not long, for in this life we are all travellers on a journey, hastening on to the same shelter.

He has outstripped us on the way, but we all travel the same road and the same hostelry awaits us all.[3]

These words could be spoken at a funeral today, or at any time in the 1600 years since they were written.

Those who have studied theology know some of the Fathers’ writings on the Faith, in particular their teaching on the Holy Trinity. St Ambrose wrote definitive works on the Faith, St Basil’s work ‘On the Holy Spirit’ was critical to the life of the Church in its struggle with the ‘Pneumatomachians’ and the finalisation of the Creed at the Second Ecumenical Council of 381. This short extract from an oration of St Gregory the Theologian gives an idea of this side of their work:

‘So it is that we worship the Father, the Son and the Holy Spirit. We observe the individual distinctions, while numbering the Godhead as One. We are careful not to confound the three into one, so that we might not fall ill with the Sabellian virus. Nor do we divide the Godhead into three different realities, in case we suffer from the Arian madness… We occupy the middle ground, observing the correct boundaries of righteousness.’[4]

Note the reference to the ‘virus’ and ‘madness’ of the heresies. The Fathers did not work in the quiet of their study: their writing was forged in the furnace of fierce, sometimes violent, conflict. The Arian Emperors were persecuting the ‘Nicaeans’ and many of the major dioceses were run by heretics. Gregory on his arrival as archbishop in Constantinople had to set up a church in a private house, as all the churches of the city were in the hands of the Arians. And at his very first Pascha in 380 the Arian mob stoned the congregation, smashed the altar and desecrated the holy vessels. One of his bishops was outraged and wanted to prosecute the aggressors. This is what St Gregory wrote to him:

Certainly what happened was dreadful, our altars were insulted, our mysteries disturbed … it is important to obtain penalties for those who have wronged us.

But it is far greater and more Godlike to bear with injuries. The former course curbs wickedness, but the latter makes men good.[5]

And he proceeds to give him many examples of forgiveness from the Scriptures.

Shortly after this St Gregory was visited bya young man, who came with a group of well-wishers when he was ill in bed. When the others left, he wept inconsolably, and Gregory wept with him, and after their tears, the man confessed that he had come with the intention of assassinating him:

‘I was shocked to hear this, but managed to say something to absolve his crime. May God save you. It is nothing special that I should be kind to you, my assassin, since I too have been saved. Your rashness has made you mine. Henceforward look to how you can be a credit to God and to myself.’[6]

We see here not only the sensitive and eloquent preacher, but a man of courage, who has the Gospel commandment to forgive deeply rooted in his heart.

You will have noticed that we know a great deal about the lives of these Fathers. They lived, of course, in momentous times and many of the events in which they were involved are recorded. But we are often given intimate insights into their thoughts and feelings from their many letters; they were all voluminous letter writers and many of these letters have been preserved, we have 366 of them ascribed to St Basil, for example. Listen to this extract from one of his letters to his friend Gregory, telling him about the beauty of his quiet retreat in Pontus:

There is a lofty mountain covered with thick woods, watered towards the north with cool and transparent streams. A plain lies beneath, enriched by the ever-flowing waters, and skirted by a rich profusion of trees, thick enough to be a fence; so as to surpass even Calypso’s island, which Homer seems to have considered the most beautiful spot on earth. However, the chief praise of the place is, that being happily disposed for produce of every kind, it nurtures what to me is the sweetest produce of all, quietness.…Does it not strike you what a foolish mistake I was near making when I was eager to change this spot for your Tiberina [near Gregory’s home at Arianzus], the very pit of the whole earth?[7]

Note the little dig about Gregory’s homeland! In an earlier letter, he said how difficult it was ‘to get quit of myself….I carry my own troubles with me’; so leaving the city ‘with its countless ills’ for the solitude of this beautiful place, was not, in itself, a solution. What is required is ‘separation from the world’ and ‘preparation of the heart’ by the unlearning of prejudices’.[8]

As leading churchmen of their day, they all had huge responsibilities for the direction, management and administration of large dioceses. St Basil established a famous monastery and his monastic rule holds to this day. Some of their letters include important theological expositions; a major discussion of the meaning of the technical terms ‘ousia’ and ‘hypostasis’, for example, is to be found in a letter of St Basil to his brother Gregory of Nyssa. Many more deal with practical issues that need resolution, advice, consolation or instruction. Some of St Basil’s letters to Amphilochios, in answer to his questions about the discipline and order of the Church, have become part of definitive canon law. Notice how he introduces the first of these letters:

Even a fool, it is said, when he asks questions is counted wise. But when a wise man asks questions, he makes even a fool wise. And this, thank God, is my own case, as often as I receive a letter from your industrious self. For we become more wise and learned than we were before by asking questions, because we are taught many things we did not know; and our anxiety to answer them acts as a teacher to us.

This is very characteristic: the Fathers never miss the chance to offer some uplifting thought on whatever topic is under consideration. Here are a few examples of the 84 canons, with their numbers, from these letters:

II The woman who purposely destroys her unborn child is guilty of murder. With us there is no nice enquiry as to its being formed or unformed. The punishment, however of these women should not be for life, but for the term of ten years. And let their treatment depend not on the mere lapse of time, but on the character of their repentance.

LVI The intentional homicide, who has afterwards repented, will be excommunicated from the sacrament for twenty years

LVII The unintentional homicide will be excluded for ten years from the sacrament.

LXXII He who has entrusted himself to soothsayers, or any such persons, shall be under discipline for the same time as the homicide[9]

It is possible in this article to give only a tiny glimpse into this vast and varied literature. All the Fathers preached homilies and wrote commentaries on the Scriptures. This major part of their work is represented in this last extract. It is from St John Chrysostom’s third homily on St Matthew, where he is dealing with the genealogy of our Lord. He turns to the extraordinary inclusion of Judah as the father of the twins by his daughter-in-law Thamar:

Why do you bring up this dreadful story with its account of unlawful intercourse? If we were recounting the family tree of a mere man, we would naturally have been silent about such a thing. But, if of God Incarnate, so far from being silent, we should make a glory of them, showing forth His tender care, and His power. Yea, it was for this cause He came, not to escape our disgraces, but to bear them away. It is not only that He took flesh upon Him, and became man, that we justly stand amazed at Him, but because He vouchsafed to have such kinsfolk, being in no respect ashamed of our evils.

B. How can we characterise these great fourth century Fathers?

They all studied at the greatest centres of learning and had a great love of learning, all could have been leaders in academic or political life: yet all embraced the life of ascetical struggle.They could move the whole Empire with their eloquence; the people flocked to hear them, applauded their brilliant homilies and recorded their words, but they did not get carried away by their own eloquence. [One thing we need to be aware of, however, is the difference between the conventions of fourth century rhetoric and those of our own times, especially in English. They gloried in hyperbole: we tend to under-statement. There have been serious mis-representations of their work, in particular of St John, who is sometimes portrayed as a father of anti-semitism, because of the words he used of the judaising Christians (not the Jews) of Antioch.] They used their eloquence, but never lost sight of the ‘one thing necessary’, their commitment to the Truth.

In very different ways, they exerted leadership: St Basil and St Ambrose through their energetic example, their organisational and diplomatic skills; St Gregory and St John through the power, subtlety and beauty of the spoken word, but all retained their humility.They loved God with the fullness of their being, knowing God’s infinite love for His world, and all showed the courage of the martyr. When the whole power of the imperial house was against them, when their tiny flock was surrounded by ravening wolves, they were not discouraged. All were prepared to witness to their Lord even if it meant death, as it did for St John, who died from ill-treatment in exile.

C. So what is their significance for us?

I suggest three answers. First, we should, like them, embrace, celebrate and draw on all true learning. All true learning is of God, of the Logos, the reason that underlies all things. Many of you have a deep knowledge in your own field of study and research. We should, like the Fathers, draw on our learning and engage full-bloodily and critically with the intellectual and cultural issues of the day.

Sometimes we hear the Three Hierarchs praised as great exemplars of the Hellenic tradition. And so they are. For them, of course, the term Ελληνες refers to the Pagans, and they were educated by the leading pagan teachers of the day: but they submitted everything to their understanding of the Christian faith. So St Gregory of Nyssa in his Life of Moses says

…there are certain things derived from profane education which should not be rejected…. Indeed moral and natural philosophy may become at certain times a comrade, friend and companion of life to the higher way, provided that the offspring of this union introduce nothing of a foreign defilement….. For example, pagan philosophy says that there is a god, but it thinks of him as material. It acknowledges him as creator, but says he needed matter for creation….good doctrines can become contaminated by profane philosophy’s absurd additions.[10]

So, secondly, we need discernment, and this we can develop by drinking deeply at the spring of the holy tradition. To know whether an idea is an ‘offspring’ of ‘foreign defilement’, we need to follow the example of the Fathers and immerse ourselves in the Holy Tradition of the Church. We may be giants in our academic studies, but remain pygmies in our theology; we can grasp the complexities of modern physics, but remain babies in our knowledge of the church. The enemies of the church often know much more than we do, as did the learned Arians of the fourth century. In one sense we need to know only the simple truths of the Gospel. St Basil said that he had ‘wasted nearly all my youth in acquiring the wisdom made foolish by God. Then, like a man roused from deep sleep, I raised my eyes to the marvellous light of the truth of the Gospel, and I perceived the uselessness of the ‘wisdom of the princes of this world, that come to nought’.[11] It is a question of priority and perspective; St Basil, in fact, made full use of the wisdom of the world, but it was always subordinated to the Gospel.

So, let us get to know the prayers and hymns, the psalms and scriptures, read the Fathers, engage with the issues. It’s not difficult today. We have people to turn to for help; we have libraries with all the books we need; on the web we can hear and read many great and helpful things. It’s not difficult. You don’t know what katavasias and apolytikia are? So find out. They are just a couple of technical terms. In your academic work you absorb 20 of these before breakfast!

And always keep in mind a central truth about knowledge, epistemology as the philosophers call it. However much we know, we never get far below the surface and our understanding is always limited; tomorrow we may come across new evidence that undermines our current theory. The Fathers were deeply aware of this. Positive statements about the faith are seen in the context of the fundamental truth that God is ‘ανέκφραστος, απερινόητος, αόρατος, ακατάληπτος, [Anaphora in the liturgy of St John Chrysostom]. Fundamental realities are beyond the grasp of our mind, and cannot adequately be expressed in words.

Thirdly, and finally, let us emulate the Fathers in their courage in the face of adversity. We tend to contrast our complex world with its scattered and weak Christian communities with the great Christian Εmpire of the fourth century. Your reading will show you the great complexity and fluidity of this period. Had Julian, the apostate Emperor, the fellow-student of Sts Basil & Gregory, not died in battle with the Persians, in the third year of his reign, the church might have sustained decades of persecution. What a tiny flock was there for Gregory in Constantinople, surrounded by ravening wolves, and the greatest preacher the Church has ever known died from ill-treatment in exile.

Reading

Nicene and Post Nicene Fathers This nineteenth century translation was re-printed in recent times and can easily be found. The quotations in this article are from here, unless otherwise indicated.

John McGuckin, St Gregory Nazianzus, an intellectual biography, SVS Press, 2001

[1] St Gregory Oration 38tr. Hopko The Winter Pascha SVS Press 1984, p 25

[2] McGuckin p 117f

[3]Letter 5. To Nektarios on the death of his son

[4] St Gregory Oration 20.5

[5] Letter to Theodore of Tyana

[6] De vita sua 1466-1471 PG 37.1129 tr McGuckin p 259

[7] Letter 14 tr. by Newman with slight modification

[8] Extracts from Letter 2

[9] Letters 188, 199 & 217

[10] tr. Classics of Western Spirituality Paulist Press 1978