|

From 'Orthodoxy and the World' www.pravmir.com Discussions and Opinions Source: Desent of the Holy Spirit Orthodox Christian Mission

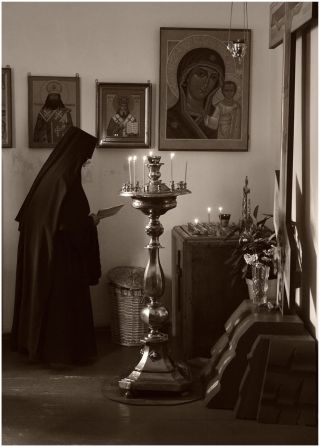

1 What is “Ritual Impurity” and Why?[1] When I entered a convent of the Russian Orthodox Church Abroad in France, I was introduced to the restrictions imposed on a nun when she has her [monthly] period. Although she was allowed to go to church and pray, she was not to go to Communion; she could not kiss the icons or touch the Antidoron; she could not help bake prosphoras or handle them, nor could she help clean the church; she could not even light the lampada or iconlamp that hung before the icons in her own cell: this last rule was explained to me when I noticed an unlighted lampada in the icon-corner of another sister. I do not remember that anyone attempted either to question or justify these strictures; we simply presumed that menstruation was a form of “impurity,” and we had to stay away from things holy so as not to somehow defile them.

2 An article written by His Holiness Patriarch Pavle of Serbia, entitled “Can a Woman Always go to Church?” [4] is often cited as a moderate opinion allowing menstruating women to participate in all but Communion and denouncing the concept of “ritual impurity.” Yet Patriarch Pavle defends another traditional restriction forbidding a woman to enter a church or participate in any sacraments for forty days after giving birth to a child . [5] This stricture, also based on the concept of “ritual impurity,” is observed in ROCOR parishes I know both in Germany and the United States. However, one can find evidence on websites of the Moscow Patriarchate that the usage is not upheld everywhere and is being questioned in Moscow-run parishes .[6] Today, in light of “feminist” theology[7] and traditionalist reactions to it,[8] it is tempting to approach the issue of “ritual impurity” in a political or social vein. Indeed, the rather degrading day-to-day implications of the above-mentioned restrictions can be taxing for any woman accustomed to the socio-political culture of the West. Nonetheless, the Orthodox Church traditionally has no socio-political agenda,[9] rendering an argument from this perspective largely irrelevant for the Church. Furthermore, the concern that something may be “degrading” for a woman is foreign to Orthodox spirituality, which focuses on humility: when we experience drawbacks, limitations, grief, etc., we learn to recognize our sinfulness and grow in our faith and dependence upon God’s saving mercy. Hence I would like to prescind from egalitarian concerns and draw your attention to the theological and anthropological implications of “ritual impurity.” Our church life is not ultimately about adhering to certain rules, reading certain prayers, doing the proper prostrations, or even about humility per se; it is about the theological and anthropological meaning of it all. By doing these things we profess a certain meaning, a certain tenet of our faith. So today I shall ask: What is the meaning of abstaining from Communion during menstruation? What does this say about the female body? What is the meaning of not setting foot in church after giving birth to a child? What statement is being made about childbirth? Most importantly, is the concept of “ritual impurity” congruent with our faith in Jesus Christ? Where did it originate and what does it mean for us today? Let us take a look at the biblical, canonical, and liturgical sources in an attempt to answer these questions.[10] The Old Testament The earliest biblical evidence to ritual restrictions for women during menstruation is found in the Old Testament, in Leviticus 15: 19-33. According to Leviticus, not only was the menstruating woman “impure”; any person who touched her also became “impure” (Lev 15: 24), resulting in a sort of impurity by contact. In later chapters of Leviticus (17-26, the “Law of Sanctity”), sexual intercourse with one’s wife at this time was strictly forbidden. Childbirth, like menstruation, was also considered defiling and subjected the woman who had given birth to similar restrictions (Lev 12). The Jews were by far not the only ones in the ancient world imposing such regulations. The pagan cults also had strictures based on a concern for “ritual purity”: menstruation was considered defiling and rendered pagan priestesses incapable of performing their cultic duties in the temples[11]; priests had to avoid menstruating women at all costs for fear of defilement[12]; the birth of a child was believed to be defiling.[13] Nonetheless the Jews were a case sui generis. Apart from their singular abhorrence for blood (Lev 15: 1-18),[14] the ancient Jews held to a belief in the dangers of female blood discharge that grew gradually, and became even stronger in later Judaism[15]: the Mishna, Tosefa, and Talmud are even more concise than the Bible on this topic.[16] The Protoevangelium of James and the New Testament At the very dawn of the New Testament the All-Holy Virgin Mary herself is subjected to the demands of “ritual purity.” According to the Protoevangelium of James, a 2nd-century apocryphal text which inspired several of the Church’s Marian feasts, the All-Holy Virgin lives in the temple from age two to twelve, when she was betrothed to Joseph and sent to reside in his house “Lest she pollute the sanctuary of the Lord” (VIII. 2).[17] When Jesus Christ began to preach, a very new message resounded in the villages of Judea – one that challenged deep-seated presumptions of pharisaic piety and of the ancient world in general. He proclaimed that it is only the evil intentions that come out of our hearts that defile us (Mk 7: 15ff). Our Savior thus placed the categories of “purity” and “impurity” wholly in the sphere of conscience[18] – in the sphere of free will toward virtue and sin – liberating the faithful from the ancient fear of defilement through uncontrollable phenomena of the material world. He himself has no qualms about talking to a Samaritan woman, something the Jews considered defiling on several levels.[19] More to our topic, the Lord does not reprimand the hemorrhaging woman for having touche d His clothes in the hope of being cured: He heals her and then praises her faith (Mt 9: 20-22). Why does Christ reveal the woman to the crowd? St. John Chrysostom answers that the Lord “reveals her faith to all, so that others would be encouraged to imitate her.” [20] The Apostle Paul likewise abandons a traditional Hebrew approach to Old-Testament regulations regarding “purity” and “impurity,” allowing for them only in the interests of Christian charity (Rom 14). It is well-known that Paul generally prefers the word. The Early Church and Early Fathers The attitude of the Early Church to the Old Testament was not a simple one and cannot be thoroughly expounded within the scope of this paper. Neither Judaism nor Christianity was a clearly separate, developed identity in the first centuries: they shared a common approach to certain things.[21] The Church clearly acknowledged the Old Testament as divinely-inspired Scripture, while at the same time distancing herself since the Council of the Apostles (Acts 15) from the prescriptions of the Mosaic Law. While the Apostolic Fathers, the first generation of church writers after the Apostles, barely touch upon the Mosaic laws concerning “ritual impurity,” these restrictions are widely discussed somewhat later, from the middle of the 2nd century. By that time it is clear that the letter of the Mosaic Law had become foreign to Christian thought, as Church writers attempt to interpret it symbolically. Methodius of Olympus (@ca. 300), Justin Martyr (@ca. 165) and Origen (@ca. 253 ) interpret levitical categories of “purity” and “impurity” allegorically, that is to say, as symbols of virtue and sin[22]; they also insist upon Baptism and the Eucharist as sufficient sources of “purification” for Christians.[23] In his treatise On the Jewish Foods, Methodius of Olympus writes: “It is clear that he who has once been cleansed through the New Birth [baptism], can no longer be stained by that which is mentioned in the Law…” [24] In a similar vein, Clement of Alexandria writes that spouses no longer need to bathe after sexual intercourse as stipulated according to the Mosaic Law “because,” Clement insists, “the Lord has cleansed the faithful through baptism for all marital relations.”[25] And yet Clement’s seemingly open attitude toward marital sexual relations in this passage is not typical of church writers at this time,[26] not even of Clement himself.[27] It was more characteristic of these writers to view all proscriptions of the Mosaic Law as purely symbolic except those concerning sex and sexuality. In fact, the early church writers had a tendency to view any manifestation of sexuality, including menstruation, marital relations, and childbirth as “impure” and thus incompatible with participation in the liturgical life of the Church. The reasons for this are numerous. In an age before the Church’s teaching had crystallized into a defined dogmatic system, there were many ideas, philosophies, and outright heresies floating in the air, some of which found their way into the writings of early Christian writers. Pioneers of Christian theology like Tertullian, Clement, Origen, Dionysius of Alexandria and others, highly-educated men of their time, were in part under the influence of the pre-Christian philosophical and religious systems that dominated the classical education of their day. For example, the so-called “Stoic axiom,” or the Stoic view that sexual intercourse is justifiable solely as a means for procreation,[28] is repeated by Tertullian,[29] Lactantius,[30] and Clement of Alexandria.[31] The Mosaic prohibition in Lev 18: 19 of sexual intercourse during menstruation thus acquired a new rationale: it was not only “defiling”; if it could not result in procreation it was sinful even within wedlock. Note in this context that Christ only mentions sexual intercourse once in the Gospel, “…and the two shall become one flesh” (Mt 9: 5), without mentioning procreation.[32] Tertullian, who embraced the ultra-ascetical heresy of Montanism in his latter years, went further than most and even considered prayer after sexual intercourse impossible.[33] The famous Origen was notoriously influenced by the contemporary eclectic Middle Platonism, with its characteristic depreciation of all things physical, and indeed of the material world in general. His ascetical and ethical doctrine, while primarily biblical, are also to be found in Stoicism, Platonism, and to a lesser degree in Aristotelianism.[34] Not surprisingly, then, Origen views menstruation as “impure” in and of itself.[35] He is also the first Christian writer to accept the Old Testament concept in Lev 12 of childbirth as something “impure.”[36] It is perhaps significant that the cited theologians came from Egypt, where Judaic spirituality peaceably coexisted with a developing Christian theology: the Jewish population, constantly diminishing from the beginning of the 2nd century in the capital city of Alexandria, exerted an often unnoticeable yet strong influence on local Christians, themselves largely Jewish converts.[37] The Syriac Didaskalia The situation was different in the Syrian capital of Antioch, where a strong Jewish presence posed a tangible threat to Christian identity.[38] The Syriac Didaskalia, a 3rd century witness to Christian polemics against Judaic traditions, forbids Christians to observe the Levitical laws, including those concerning menstruation. The author admonishes women who abstain from prayer, Scripture lessons, and Eucharist for seven days during menstruation: “If you think, woman, that you are stripped of the Holy Spirit during the seven days of your menstruation, then if you die at this time, you will depart thence empty and without hope.” The Didaskalia goes on to assure the woman of the presence The Council of Gangra About a century later, toward the middle of the 4th century, we find canonical evidence against the concept of “ritual impurity” among the legislation of the local Council convened ca. AD 341[41] in Gangra (105 km northeast of Ankara) on the northern coast of Asia Minor, which condemned the extreme asceticism of the followers of Eustathius of Sebaste (@post-377).[42] The Eustathian monastics, inspired by dualistic and spiritualistic teachings widespread in Syria and Asia Minor at that time, denigrated marriage and the married clergy. Against this Canon 1 of the Council reads: “If anyone disparages marriage, or abominates or disparages a woman sleeping with her husband notwithstanding that she is faithful and reverent, as though she could not enter the kingdom, let him be anathema.” [43] The Eustathians refused to receive the Eucharist from married clergy out of a concern for " ritual purity,"[44] a practice likewise condemned by the Council, in its fourth canon: “If anyone discriminates against a married presbyter, on the ground that he ought not to partake of the offering when that presbyter is conducting the Liturgy, let him be anathema.” [45] Interestingly, Eustathianism was an egalitarian movement, promoting a complete leveling of the sexes.[46] The female followers of Eustathius were hence encouraged to cut their hair and dress like men to overcome every semblance of femininity, which, like all aspects of human sexuality, was considered “defiling.” The Council condemns this practice in its 13th canon: “If for the sake of supposedly ascetic exercise any woman change apparel, and instead of the usual and customary woman’s apparel, she dons men’s apparel, let her be anathema.”[47] In rejecting Eustathian monasticism, the Church rejected the view of sexuality as “defiling,” defending both the sanctity of marriage and of the God-created phenomenon called woman. The Canons of the Egyptian Fathers In the light of these fully Orthodox ancient canons, how can the Church have canons in full force today that support the concept of “ritual impurity” unequivocally?[48] As previously noted, Church literature, including canonical texts, did not materialize in a vacuum, but within the socio-cultural, historical reality of the ancient world, which very much believed in and demanded “ritual purity.”[49] The earliest canon restricting women in a state of “impurity” (?ν ?φ?δρ?) is Canon 2 of Dionysius of Alexandria (@264), written in 262 a.d.: "Concerning menstruous women, whether they ought to enter the temple of God while in such a state, I think it superfluous even to put the question. For, I think, not even themselves, being faithful and pious, would dare when in this state either to approach the Holy Table or to touch the body and blood of Christ. For not even the woman with a twelve years’ issue would come into actual contact with Him, but only with the edge of His garment, to be cured. There is no objection to one’s praying no matter how he may be or to one’s remembering the Lord at any time and in any state whatever, and petitioning to receive help; but if one is not wholly clean (? µ? π?ντη καθαρ?ς) both in soul and in body, he shall be prevented from coming up to the Holy of Holies”.[50] Note that Dionysius, like the Syriac Didaskalia, refers to the woman with the flow of blood in Mt 9: 20-22, but comes to precisely the opposite conclusion: that a woman cannot receive communion. It has been suggested that Dionysius was actually forbidding women to enter the sanctuary (altar’) and not the church proper.[51] This hypothesis not only contradicts the text of the cited canon; it also falsely presumes that the laity once received communion in the sanctuary. Recent liturgical scholarship has dispensed with the notion that the laity ever received the sacrament in the sanctuary.[52] So Dionysius meant precisely what he wrote, and precisely as many generations of Eastern Christians have understood him[53]: a menstruating woman is not to enter “the temple of God,” for she is “not wholly clean (? µ? π?ντη καθα=C F?ς) both in soul and in body.” One wonders whether this suggests all other Christians are wholly “clean,” or katharoi. Hopefully not, since the Church denounced “those who call themselves katharoi” or “the clean ones,” an ancient sect of the Novatians, at the First Ecumenical Council, Nicaea I in 325 a.d.[54] Orthodox commentators of the past and present have also explained Dionysius’ canon as somehow connected to a concern for begetting children: the 12th century commentator Zonaras (post-1159 a.d.), while rejecting the concept of “ritual impurity,” comes to the bewildering conclusion that the real reason for these restrictions against women is “to prevent men from sleeping with them…by way of providing for children being begotten.”[55] So, women are stigmatized as “impure,” banned from the church and Holy Communion to prevent men from sleeping with them? Leaving aside the sex-only-for-procreation premise of this argument, it raises some other, more obvious questions: are men somehow more likely to sleep with a woman who has gone to church and received the sacrament? Why, then, must the woman abstain from Communion? Some priests in Russia offer another explanation: women are too tired in this state to listen attentively to the prayers of the liturgy and therefore cannot prepare themselves sufficiently for Holy Communion.[56] The same reasoning is proposed for women who have given birth: they need to rest for forty days.[57] So should Communion be withheld from all tired, ill, elderly, and otherwise weak people? How about the hearing-impaired? Be that as it may, there are several other canonical texts restricting women as “impure”: Can. 6-7 of Timotheus of Alexandria (381 AD), who extends the restriction to baptism[58] and Canon 18 of the so-called Canons of Hippolytus, regarding women who have given birth and midwives.[59] Both these canons, like Canon 2 of Dionysius, are notably of Egyptian provenance. St. Gregory the Great Things were not much different in the West, where Church practice generally viewed menstruating women as “impure” until the turn of the 6th/7th century.[60] At this time St. Gregory the Great, Pope of Rome (590-604 a.d.), the Church Father to whom tradition ascribes (wrongly) the composition of the Liturgy of the Presanctified Gifts, expressed a different opinion on the matter. In 601, St. Augustine of Canterbury, the “Apostle of England,” (@604) wrote to St. Gregory and asked whether menstruating women should be allowed to go to church and receive Communion. I shall cite St. Gregory’s response at length: A woman should not be forbidden to go to church. After all, she suffers this involuntarily. She cannot be blamed for that superfluous matter that nature excretes…She is also not to be forbidden to receive Holy Communion at this time. If, however, a woman does not dare to receive, for great trepidation, she should be praised. But if she does receive she should not be judged. Pious people see sin even there, where there is none. Now one often performs innocently that which originates in a sin: when we feel hunger, this occurs innocently. Yet the fact that we experience hunger is the fault of the first man. The menstrual period is no sin; it is, in fact, a purely natural process. But the fact that nature is thus disturbed, that it appears stained even against human will – this is the result of a sin…So if a pious woman reflects upon these things and wishes not to approach communion, she is to be praised. But again, if she wants to live religiously and receive communion out of love, one should not stop her.[61] In the Early Middle Ages the policy laid down by St. Gregory fell into desuetude and menstruating women were restricted from Communion and often instructed to stand before the entrance of the Church.[62] These practices were still common in the West as late as the 17th century.[63] “Ritual Impurity” in Russia As for the history of such practices in Russia, the concept of “ritual impurity” was known to the pagan Slavs long before their Christianization. Pagan Slavs, like ancient pagans in general, held that any manifestation of sexuality was ritually defiling.[64] This belief remained virtually unchanged in Old Rus’ after its baptism. The Russian Church had particularly strict rules concerning female “impurity.” In the 12th century “Inquiry of Kyrik,” Bishop Nifont of Novgorod (1130-1156 a.d.) explains that if a woman happened to give birth to a child inside a church, the church had to be sealed for three days, then re-consecrated by a special prayer.[65] Even the wife of the tsar, the tsaritsa, would give birth outside her living quarters, in the bathhouse or “myl’nja” (banja) so as not to defile an inhabited building. After the child had been born, no one could leave or enter the Bathhouse until the priest had arrived to read the “cleansing” prayer from the Trebnik. Only after this prayer had been read could the father enter and see his child.[66] If a woman's period began while she was standing in church, she had to leave immediately. Failure to do so resulted in a penance of six months fasting, with fifty prostrations a day.[67] Even when women were not in a state of “impurity,” they received communion not at the “Royal” Doors with the male laity, but separately, at the Northern Doors.[68] The Prayers of the Trebnik The special prayer of the Trebnik or Book of Needs of the Russian Orthodox Church, read even today on the first day upon the birth of a child, petitions God to “cleanse the mother of all defilement” (ot skverny o?isti) and continues: “…and forgive Your handmaid [mother’s name] and all the house in which the child has been born, and all who have touched her, and all who find themselves here…”[69] One might ask, why do we ask forgiveness for all the house, for the mother, and for all “who have touched her” (prikosnuvšimsja ej)? Well, I know that the Levitical laws contained the notion of impurity by contact. So I know why the faithful of the Old Testament would consider it a sin Today it is often said that a woman stays out of church for forty days after giving birth because of physical fatigue. However, the cited text speaks not of her capacity to participate in liturgical life, but of her worthiness. The birth (not conception) of her child has, according to these prayers, resulted in her physical and spiritual defilement (skverna). This is similar to the reasoning of Dionysius of Alexandria about menstruation: it makes a woman “not wholly clean both in soul and in body.” Recent Developments in Other Orthodox Churches Not surprisingly, some Orthodox Churches are already moving to modify or remove euchological texts based on dogmatically indefensible concepts of childbirth, marriage, and “impurity.” I cite the decision of the Holy Synod of Antioch held in Syria on May 26, 1997 under the leadership of His Beatitude Patriarch Ignatius IV: “It was decided to give the Patriarch authorization to modify the texts of the small euchologion concerning marriage and its sacredness; prayers connected with women who give birth and enter church for the first time; and texts connected with the funeral service.”[71] A theological conference convened on Crete in 2000 came to similar conclusions: Theologians should…write simple and appropriate explanations of the churching service and adapt the language of the rite itself to reflect the theology of the Church. This would be helpful to men and women who need to be given the true meaning of the service: that it exists as an act of offering and blessing for the birth of a child, and20that it should be performed as soon as the mother is ready to resume normal activity outside her home… We urge the Church to reassure women that they are welcome to receive Holy Communion at any liturgy when they are spiritually and sacramentally prepared, regardless of what time of month it may be.[72] 15 Conclusion I shall conclude briefly, since the texts have spoken for themselves. A close look at the origins and character of the concept “ritual impurity” reveals a rather disconcerting, fundamentally non-Christian phenomenon in the guise of Orthodox piety. Regardless of whether the concept entered church practice under direct Judaic and/or pagan influences, it finds no justification in Christian anthropology and soteriology. Orthodox Christians, male and female, have been cleansed in the waters of baptism, buried and resurrected with Christ, Who became our flesh and our humanity, trampled Death by death, and liberated us from its fear. Yet we have retained a practice that reflects pagan and Old-Testament fears of the material world. This is why a belief in “ritual impurity” is not primarily a social issue, nor is it primarily about the depreciation of women. It is rather about the depreciation of the Incarnation of our Lord Jesus Christ and its salvific consequences. [1] This paper appeared as an article in St Vladimir’s Theological Quarterly 52:3-4 (2008) 275-92. [2] Nastol’naja kniga svjaš8 Denno-cerkovnoslužitelja (Char’kov 1913), 1144 [3] See the questions-answers of Fr. Maxim Kozlov on the website of the St. Tatiana Church in Moscow: www.st-tatiana.ru/index.html?did=389 (15 January 2005). Cf. A. Klutschewsky, “Frauenrollen und Frauenrechte in der Russischen Orthodoxen Kirche,” Kanon 17 (2005) 140-209. [4] First published in Russian and German in the quarterly of the ROCOR Diocese of Berlin in Germany: “Možet li ženš?ina vsegda poseš?at’ xram?” Vestnik Germanskj Eparxii 2 (2002) 24-26 and later online: http://www.rocor.de/Vestnik/20022/. [5] This stricture officially holds according to the Trebnik or “Book of Needs” of the Russian Orthodox Church. See English transl.: Book of Needs of the Holy Orthodox Church, trans. by G. Shann, (London 1894), 4-8. [6] See the website of MP parishes in the US: www.russianchurchusa.org/SNCathedral/forum/D.asp?n=1097; also www.ortho-rus.ru/cgi-bin/ns. [7] See the Conclusion of the Intra-Orthodox Consultation on he Place of the Woman20in the Orthodox [8] For example, K. Anstall, “Male and Female He Created Them”: An Examination of the M ystery of Human Gender in St. Maximos the Confessor Canadian Orthodox Seminary Studies in Gender and Human Sexuality 2 (Dewdney 1995), esp. 24-25. [9] Cf. G. Mantzaridis, Soziologie des Christentums (Berlin 1981), 129ff; id., Grundlinien christlicher Ethik (St. Ottilien 1998), 73. [10] The following excellent study on the historical and contemporary canonical sources concerning “ritual im/purity“ escaped my attention when I wrote this article: E. Synek, „Wer aber nicht völlig rein ist an Seele und Leib…” Reinheitstabus im Orthodoxen Kirchenrecht,” Kanon Sonderheft 1, (München-Egling a. d. Paar 2006). [11] E. Fehrle, Die kultische Keuschheit im Altertum in Religionsgeschichtliche Versuche und Vorarbeiten 6 (Gießen 1910), 95. [12] Ibid., 29. [13] Ibid., 37. [14] Cf. R. Taft, “Women at Church in Byzantium: Where, When – and Why?” Dumbarton Oaks Papers 52 (1998) 47. [15] I. Be’er, “Blood Discharge: On Female Im/Purity in the Priestly Code and in Biblical Literature,” in A. Brenne r (ed.), A Feminist Companion from Exodus to Deutoronomy (Sheffield 1994), 152-164. [16] J. Neusner, The Idea of Purity in Ancient Judaism (Leiden 1973). [17] M. James, The Apocryphal New Testament (Oxford 1926), 42. Cf. Taft, “Women” 47. [18] D. Wendebourg, “Die alttestamentli chen Reinheitsgesetze in der frühen Kirche,“ Zeitschrift für Kirchengeschichte 95/2 (1984) 149-170. [19] Cf. „Samariter,“ Pauly-Wissowa II, 1, 2108. [20] In Matthaeum Homil. XXXI al. XXXII, PG 57, col. 371. 5 “holy” (?γιος) to the word “pure” to express a Christian’s closeness to God, thus avoiding Old-Testament preconceptions (Rom 1: 7; 8: 27; 1 Cor 6: 1; 7: 14; 2 Cor 1: 1 etc.) [21] E. Synek, “Zur Rezeption Alttestamentlicher Reinheitsvorschriften ins Orthodoxe Kirchenrecht,” Kanon 16 (2001) 29. [22] See references in Wendebourg, “Reinheitsgesetze” 153-155. [23] Justin, Dialog. 13; Origen, Contr. Cels. VIII 29. [24] V, 3. Cf. Wendebourg, “Reinheitsgesetze” 154. [25] Stromata III/XII 82, 6.6 [26] With the notable exception of St. Irenaeus, who did not see sexuality as a result of the fall. See Adv. [27] J. Behr, Asceticism and Anthropology in Irenaeus and Clement (Oxford 2000), 171-184. [28] S. Stelzenberger, Die Beziehungen der frühchristlichen Sittenlehre zur Ethik der Stoa. Eine moralgeschichtliche Studie (München 1933), 405ff. [29] De monogamia VII 7, 9 (CCL 2, 1238, 48ff). [30] Div. Institutiones VI 23 (CSEL 567, 4 ff). [31] Paed. II/X 92, 1f (SC 108, 176f). [32] Cf. Behr, “Marriage and Asceticism,” 7. [33] De exhortatione castitatis X 2-4 (CCL 15/2, 1029, 13ff). Cf. Wendebourg, “Reinheitsgesetze” 159.7 [34] Innumerable studies have been written on Origen’s relationship with the philosophical currents of his [35] Cat.in Ep. ad Cor. XXXIV 124: C. Jenkins (ed.), “Origen on 1 Corinthians,” Journal of Theological Studies 9 (1908) 502, 28-30. [36] Hom. in Lev. VIII 3f (GCS 29, 397, 12-15). [37] See L. W. Barnard, “The Background of Early Egyptian Christianity,” Church Quarterly Rev. 164 (1963) 434; also M. Grant, The Jews in the Roman World (London 1953), 117, 265. Cf. references in Wendebourg, “Reinheitsgesetze” 167. [38] See M. Simon, Recherches d’Histoire Judéo-Chrétenne (Pa ris 1962), 140ff., and M. Grant, ”Jewish [39] Didaskalia XXVI. H. Achelis-J. Fleming (eds.), Die ältesten Quellen des orientalischen Kirchenrechts 2 (Leipzig 1904), 139. [40] Ibid. 143. [41] On the date see: T. Tenšek, L’ascetismo nel Conci lio di Gangra: Eustazio di Sebaste nell’ambiente [42] J. Gribomont, “Le monachisme au IVe s. en Asie Mineure : de Gangres au messalianisme,” Studia Patristica 2 (Berlin 1957), 400-415. [43] P. Joannou, Fonti. Discipline générale antique (IVe- IXes.), fasc. IX, (Grottaferrata-Rome 1962), t. I, 2, 89. English trans. from The Rudder (Pedalion), trans. by D. Cummings (Chicago 1957), 523. [44] See Tenšek, L’ascetismo 17-28.9 [45] Joannou, Discipline 91; The Rudder 524. [46] Tenšek, L’ascetismo 28. [47] Joannou, Discipline 94; The Rudder 527. [48] On the later development in Byzantium see P. Viscuso, „Purity and Sexual Defilement in Late Byzantine Theology,” Orientalia Christiana Periodica 57 (1991) 399-408. [49] Cf. H. Hunger, “Christliches und Nichtchristliches20im byzantinischen Eherecht,“ Österreichisches Archiv für Kirchenrecht 3 (1967) 305-325. 10 [50] C. L. Feltoe (ed.), The Letters and Other Remains of Dionysius of Alexandria (Cambridge 1904), 102-103. For date and authenticity see P. Joannou, Discipline générale antique (IVe- IXes.) 1-2 (Grottaferratta-Rom 1962), 2, 12. Translation adapted from The Rudder 718. [51] Patriarch Pavle, “Možet li ženš?ina” 24. [52] R. F . Taft, The Communion, Thanksgiving, and Concluding Rites (Rome202008), 205-207 (in press). [53] See the commentary of Theodore Balsamon (ca. 1130/40-post 1195) on this canon: In epist. S. Dionysii Alexandrini ad Basilidem episcopum, can. 2, PG 138: 465C-468A. [54] Can. 8, Rallis-Potlis II, 133. [55] English translation in The Rudder 719. Zonaras is repeated verbatim by Patriarch Pavle, “Možet li [56] Klutschewsky, “Frauenrollen” 174. [57] See the questions-answers of Fr. Maxim Kozlov on the website of the St. Tatiana Church in Moscow: www.st-tatiana.ru/index.html?did=389. [58] CPG 244; Joannou, Discipline II, 243-244, 264. [59] W. Riedel, Die Kirchenrechtsquellen des Patriarchats Alexandrien (Leipzig 1900), 209. See English [60] P. Browe, Beiträge zur Sexualethik des Mittelalters, Breslauer Studien zur historischen Theologie XXIII (Breslau 1932). On the development of the concept of „ritual im/purity“ in the West in connection with priestal celibacy see H. Brodersen, Der Spender der Kommunion im Altertum und Mittelalter. Ein Beitrag zur Geschichte der Frömmigkeitshaltung, UMI Dissertation Services, (Ann Arbor 1994), 23-25, 132.12 [61] PL 77, 1183. On authenticity see Browe, Beiträge 10, reference 67. [62] On the debate in the West as to whether menstruating women could take part in liturgical life see: J. [63] Ibid., 14. [64] E. Levin, Sex and Society in the World of the Orthodox Slavs 900-1700 (Ithaca-London 1989), 46. [65] Voprosy Kirika, in Russkaja Istori?eskaja Biblioteka VI (St. Petersburg 1908), 34, art. 46. 13 [66] I. Zabelin, Domašnij byt russkix carej v XVI I XVII stoletijax (Moscow 2000), vol. II, 2-3. [67] Trebnik (Kiev 1606), ff. 674v-675r. Cited by Levin, Sex and Society 170. [68] B. Uspenskij, Car’ i Patriarx (Moscow 1998), 145-146, notes 3 and 5. [69] “Molitva v pervyj den’, po vnegda roditi žene otro?a,” Trebnik (Moscow 1906), 4v-5v. [70] “Molitvy žene rodil’nice po 40-ti dnex,” ibid., 8 -9.14 [71] Synek, “Wer aber nicht,” 152. [72] Eadem, 148. [73] Department of Religious Education, Orthodox Church in America (ed.), Women and Men in the Church. A Study on the Community of Women and Men in the Church (Syosset, New York 1980), 42-43.

© Copyright 2004 by 'Orthodoxy and the World' www.pravmir.com |