Father Thomas, many people recognize there is a value in forgiving and being forgiven, but see it only on the human level, without a theological dimension. Would you say forgiveness is a divine act?

Father Thomas, many people recognize there is a value in forgiving and being forgiven, but see it only on the human level, without a theological dimension. Would you say forgiveness is a divine act?

If a person is inspired by the spirit of God, he or she can forgive, certainly. People can forgive. But I’m not sure you can say that in general there is the feeling that forgiveness is of value. I have met people who would say, “I don’t care. I can go on and live my life; it really doesn’t matter to me. If I’m not bothering you and you aren’t bothering me, why be reconciled?” This is plain indifference.

Another reason why people don’t value forgiveness is that they consider it to be collusion with evil. They feel that if a person has done something really terrible, he or she should be reminded of it until death, and further, that the evil should be avenged. And of course, most of us feel that any offense committed against us is irreparable. Nothing that the other person does can ever cancel it. If you kill my child, for example, there is nothing you can do in reparation, and for me to forgive would simply be to condone the evil. So I’m not sure that most people value forgiveness.

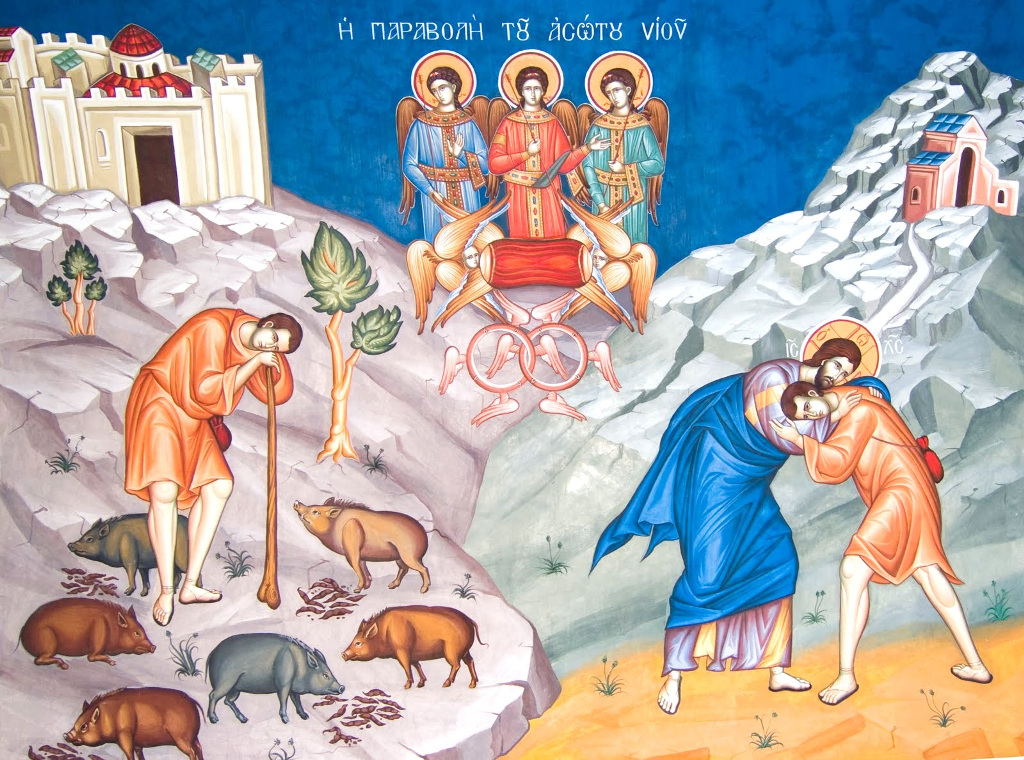

When you look at it from the point of view of justice, there is no reason for forgiveness. Only if God exists and we realize that there is either a world with evil or no world at all, only then can we understand that we are going to have to undergo the trial of evil. But if that is not there, I don’t know why anyone would forgive. Or want to. But I do think that people who are not believers in God, by the fact they are made in God’s image, can have the sense that reconciliation is better than allowing the evil to go on. By definition, forgiveness is breaking the chain of evil, beginning by recognizing that evil really has been done. People tend to think forgiveness means something bad was not really done, that a person didn’t understand the consequences, or whatever. If that were the case, there would be no need for forgiveness; it could be seen simply as a mistake. Forgiveness has to admit, and rage over, and weep over a real evil, and only then say, “We are going to live in communion one with another. We are going to carry on.” Never forgetting — you can’t, at any rate — but carrying on in a spirit of love without letting the evil poison the future relationship. Certainly that is what happens theologically. The striking thing in the Gospel is that God refuses to let evil destroy the relationship. Even if we kill him, he will say, “Forgive them.”

Implied in what you say is that relationship is the highest aim, and that an obstacle to relationship is what calls the need for forgiveness.

Implied in what you say is that relationship is the highest aim, and that an obstacle to relationship is what calls the need for forgiveness.

I prefer the word communion to relationship. The Orthodox approach is that we are made in the image and likeness of God, and that God is a Trinity of persons in absolute identity of being and of life in perfect communion. Therefore, communion is the given. Anything that breaks that communion destroys the very roots of our existence. That’s why forgiveness is essential if there is going to be human life in the image of God. We are all sinners, living with other sinners, and so 70 times 7 times a day we must re-establish communion — and want to do so. The desire is the main thing, and the feeling that it is of value.

The obsession with relationship — the individual in search of relationships — in the modern world shows there is an ontological crack in our being. There is no such thing as an individual. He was created, probably, in a Western European university. We don’t recognize our essential communion. I don’t look at you and say, “You are my life.”

Modern interpretations of the commandment in the Torah reflect this individualistic attitude. The first commandment is that you love God with all your mind, all your soul, and all your strength, and the second is that you love your neighbor as yourself. The only way you can prove you love God is by loving your neighbor, and the only way you can love your neighbor in this world is by endless forgiveness. So, “love your neighbor as yourself.” However, in certain modern editions of the Bible, I have seen this translated as, “You shall love your neighbor as you love yourself.” But that’s not what it says.

I recall a televised discussion program in which we were asked what was most important in Christianity. Part of what I said was that the only way we can find ourselves is to deny ourselves. That’s Christ’s teaching. If you cling to yourself, you lose yourself. The unwillingness to forgive is the ultimate act of not wanting to let yourself go. You want to defend yourself, assert yourself, protect yourself. There is a consistent line through the Gospel — if you want to be the first you must will to be the last. The other fellow, who taught the psychology of religion at a Protestant seminary, said, “What you are saying is the source of the neuroses of Western society. What we need is healthy self-love and healthy self-esteem.” Then he quoted that line, “You shall love your neighbor as you love yourself.” He insisted that you must love yourself first and have a sense of dignity. If one has that, forgiveness is either out of the question or an act of condescension toward the poor sinner. It is no longer an identification with the other as a sinner, too. I said that of course if we are made in the image of God it’s quite self-affirming, and self-hatred is an evil. But my main point is that there is no self there to be defended except the one that comes into existence by the act of love and self-emptying. It’s only by loving the other that myself actually emerges. Forgiveness is at the heart of that.

As we were leaving a venerable old rabbi with a shining face called us over. “That line, you know, comes from the Torah, from Leviticus,” he said, “and it cannot possibly be translated ‘love your neighbor as you love yourself.’ It says, ‘You shall love your neighbor as being your own self’.” Your neighbor is your true self. You have no self in yourself.

After this I started reading the Church Fathers in this light, and that’s what they all say — “Your brother is your life.” I have no self in myself except the one that is fulfilled by loving the other. The Trinitarian character of God is a metaphysical absolute here, so to speak. God’s own self is another — His Son. The same thing happens on the human level. So the minute I don’t feel deeply that my real self is the other, then I’ll have no reason to forgive anyone. But if that is my reality, and my only real self is the other, and my own identity and fulfillment emerges only in the act of loving the other, that gives substance to the idea that we are potentially God-like beings. Now, if you add to that that we are all to some degree faulty and weak and so on, that act of love will always be an act of forgiveness. That’s how I find and fulfill myself as a human being made in God’s image. Otherwise, I cannot. So the act of forgiveness is the very act by which our humanity is constituted. Deny that, and we kill ourselves. It’s a metaphysical suicide.

You are making a distinction here between the individual and the person.

The individual is the person that refuses to love. When a person refuses to identify in being and value with “the least,” even with “the enemy,” then the person becomes an individual, a self enclosed being trying to have proper relationships — usually on his or her own terms. But again, we would say that the person only comes into existence by going out of oneself into communion with the other. So my task is not to decide whether or not I will be in relationship with you but to realize that I am in communion with you: my life is yours, and your life is mine. Without this, there is no way that we are going to be able to carry on.

Forgiveness is not an achievement, an act, so much as the development of an understanding of reality?

It is a decision in the sense that you have to will it. You have to choose life. A person can choose death by not forgiving. So there is a sense in which you can destroy yourself by not saying “yes” to the reality that actually exists. That’s the choice: “yes” or “no” to what truly exists. Forgiveness is the great “yes.” So there is a choice. In the Greek patristic tradition, the more a person is a person, the more we realize and will our communion with others in the act of love, the less we choose. So the freer we are, the less choice we have.

That’s almost opposite to the post-Enlightenment, secular Western thought. We tend to think the freer we are, the more choice we have. For example, if you would sin against me and I want to love with the love of God, then I do not have a choice whether or not I should forgive you, I only have a choice whether or not I will. And I must, if I want to be alive. If I were truly holy, I wouldn’t even choose — it would be a spontaneous act.

As an individual, if someone or insults me offends me or betrays me, it is impossible to forgive them, lacking this understanding of the reality of our interconnectedness. So this understanding is needed.

Otherwise there is no reason to forgive.

There is a reason, because one suffers from not being able to forgive.

Yes, but within the categories of what we would call “the fallen world,” there is no reason, unless communion enters into the picture.

I think that in our culture the willingness to admit there is real evil is difficult for us — it is such a violent and awesome position towards life. Of course, people in tremendous pain — rape victims, incest victims, etc. — have to forgive if they are going to go on living. But the main forgiving that needs doing in everybody’s life, the central act of forgiveness and one that indicates spiritual maturity in every case without exception, is the forgiveness of the parents. We tend either to blame parents or idealize them — both of which cripple life. In order to forgive them, one must first admit the offense, and that may mean enduring incredible pain. Rage and sadness have to be faced in order to forgive. The reason that we can’t forgive is because we don’t want to face the pain and rage, to admit what really happened.

So people try to live without facing all this. Or when that becomes impossible, it can mean trying to lose oneself in a cult or other form of collective. You sell your soul so that you don’t have to choose anymore. This wish to escape is what fueled a great deal of what happened in the ’60s and since. People wanted to lose themselves; they couldn’t handle the individual freedoms, because they weren’t on a deep enough level. So there was a flight. I think even the feminist movement is a response to this. In The Flight from Woman, Karl Stern shows that in Western culture there has been an almost pathological flight from the feminine, from woman, which means a flight from communion, a flight from the other. The individualistic, radical, fallen, male values became the values for the culture as a whole, and that’s the cause of the Western neuroses.

The burden of freedom is cruel — “how cruel is the love of God.” But that’s what we are called for. The individualistic or the collectivistic solutions will not work. We are persons made for free and voluntary communion in love and truth in reality with other persons. This means that in the way we experience life, mercy and forgiveness are at the heart of it, beginning in one’s own family. That’s where it’s so, so painful.

My feeling, being a radical Orthodox Christian, is that God is not removed from the world but rather enters into the world and gets nailed to a cross. Unless we accept Christ crucified, which is a scandal to those who want God to be some kind of power figure and total foolishness to those who want it all to fall into place intellectually, within our terms, there’s no Gospel. But if Christ crucified is at the heart of the matter, then evil is real and forgiveness is real and freedom is real, and there’s no other way to deify life but through an act of mercy.

There are some who feel that to understand all is to forgive all. If we could see the entire chain of causality, there would be no reason to forgive, because we would understand.

I wouldn’t agree. Actually, when you see things clearly, you can see that certainly we are victimized. There’s a woman I’m thinking of who must forgive her father and her uncle for raping her over a period of years when she was a child. Once she begins to see things, she can admit that her father was also a victim, that in many ways he was conditioned — that’s what the Bible means when it says sins visited to the fourth generation. There is such a thing as a tradition of evil. That’s why I like to use the expression that forgiveness is breaking the chain of evil. But everyone is given that possibility to break that chain. As long as I’m understanding, justifying, explaining, I become just one more link in the chain of evil.

Could you explain what you mean by evil?

In Orthodox theology, we speak about evil, or sin, as either voluntary or involuntary — conscious or unconscious. We would not define sin as the cold-blooded, freely sovereign and intellectual act whereby I perpetrate some evil — destroy someone’s life, for example. It’s much more complicated. One of the points of the Adam story is that we are not born in Paradise. It is anything but Paradise. A child of a hysterical, drug-addicted parent is going to be born drug addicted as well. There is a tendency toward “evil” in us, biologically, psychologically, genetically. Father Alexander Schmemann used to say that the spiritual life consists in how you deal with what you have been dealt. We’ve all been dealt something. Our theological claim is that where you have a good measure of faith, and love, and forgiveness, you can restore human nature. You can pass on a more healthy, integrated, peaceful, joyful humanity to your progeny. You can be a presence of forgiveness and mercy, but you can also be a presence of the opposite. In order to be a presence of mercy, you must admit tragedy; you can’t just explain it away in terms of genetics, or economics.

There is a freedom: what you do with what you have. It’s not a sovereign freedom as though I were just emerging as a pristine pure angel. No. But the point is if you could see the causes and influences, you would come to the conclusion that there is a great deal of victimization, but at the same time, there are opportunities for people to break the chain of evil, to forgive and not to allow it to go on. Sartre says you make a choice every second. A choice about what? A choice about what you are going to do about where you are. At the very heart of that choice is always going to be an act of forgiveness.

In The Pillar of Fire, Karl Stern writes that what the modern person cannot accept is forgiveness and grace. We would rather take our punishment, as it were. God says, “No, I forgive you whether you like it or not.” That’s the only fire of hell — this loving forgiveness of God. That’s why Jesus says there is only one unforgivable sin — the blasphemy of the Holy Spirit. And what is that? It is the unwillingness to be forgiven and to forgive. The proud cannot accept grace.

Much is being written about the need to forgive oneself. Does that make sense in Christian terms?

Of course. Forgiving oneself means accepting forgiveness from God — and from other people. Evagrios of Pontus, a fourth-century writer, said that there are in us many selves, really, but at base there are two: the real self, which is the Christ-self, and a legion of other selves, which are the Adamic selves. What happens when we hear the word of grace is that we are split down the middle. We don’t want grace because of the pain we have to face, the fears and so on. But one of the things that happens — one of the lies of the Devil, so to speak — is the conviction that we are not worth it. It isn’t for us. We are too bad, worthless. Then there comes a point, as Evagrios said, when the Christ-self needs to be convinced that “yes, I exist, and I am acceptable,” and so to have pity and mercy on those other selves.

Do you see a difference between evil or sinful acts and a larger attitude that chooses darkness rather than light? Evil is not outside of us, isn’t that so?

For many people evil resides in someone else. But I think your distinction is very good, because our understanding of the Christian view is that we will sin until we die. Even baptism is for the forgiveness of sins “all the days of our life.” Baptism puts us in the context of forgiveness and mercy, which then allows what is called the invisible warfare, the unseen struggle, to go on. You are going to be sinful — that’s why Jesus says “seventy-times-seven.” It is inherent in the human life. Sin is to be expected, but the loving of the darkness is not.

In the Christian view, we are reconciled, we are forgiven. Paul Tillich, in a sermon on the parable of the sinful woman and the Pharisee, points out that repentance comes after being forgiven. It is not a payment in order to be forgiven.

It’s both. However, it’s important from our perspective what the woman in the parable then does. She does not live happily ever after but enters into a life of tremendous struggle.

Chrysostom says you are baptized in order to struggle. Take Mary of Egypt, the classic example of the forgiven harlot: she went into the desert and wept the rest of her life, not to win God by her tears, or to earn forgiveness; not to make reparation; but out of the love of God for being liberated and for the sense of what sin really is and the desire not to fall into it again. One problem in both the liberal and the fundamentalist forms of Christianity is the absence of an ongoing ascetic dimension. If you don’t have to pay for your sins because Jesus has, this can open the door to a life of profligacy. The more liberal line is: this is the way I am; this is the way God made me. God loves me, God forgives me, and so there’s nothing for me to do but carry on with my life.

What do you mean by the ascetic dimension?

It is making nothing an end in itself except God, that is, ordering the natural passions to their proper end, which is God himself, and love itself. The passions are part of our nature but must be directed in the service of love, love meaning the good of the other, the affirmation of the other. This nature must affirm the truth, the reality of things the way they are. The metaphysical base is a communion of love and being and truth for which we have been created. To say “yes” to that is the deified life. But to say “yes” to that, in the fallen world, means that you must, as Saint Paul says, crucify the flesh with its passions and desires. You must kill the ego. The “old Adam” has to die, and he always dies kicking and screaming. The multiplicity of these false selves must be exposed, and that is not easy. The evil of other people has to be named and forgiven, which is also not easy.

In the short stories of Flannery O’Connor, you find that the moment of grace is usually a violent moment. To see things clearly, to realize, as O’Connor says, that “even the virtues will be burnt up,” very often requires an incredibly violent act. We often need to be shaken into that realization. It seems to me that that’s the meaning in the scriptures of the trials and sufferings and afflictions and so on — to have people realize what and who they are, really. That’s the ascetic dimension, because the minute a person says, “I will work to show mercy,” every devil in hell will work to try to stop him.

You spoke of the division in us between the Christ-self and the legion of other selves — two natures at war within us. Is it that one nature has ultimately to be transformed? You also spoke about a person who is free and yet has no choice — this is a totally transformed being, isn’t it?

We would say there’s a human nature that when it is truly itself is full of the grace of God and in communion with God and is, therefore, deified and becomes one with the divine nature. On the other hand, there is the human nature that is broken, fragmented, estranged from its real foundation and in need of salvation. The transforming power of grace is there. But in a sense, it takes all of time to be deified. There are no miracles on this level. The degree of suffering that has to take place is very great.

It’s an incarnated struggle on this level.

Yes, and I believe it can’t be done alone. You need a community.

Our culture places great emphasis on improving oneself. There is a difference between that and being made whole, being brought to your true nature.

The saints speak about spiritual hedonism, where you want peace and joy but you don’t want reality. That’s why Saint Paul says that you can give your body to be burned but if you have not love, you are nothing.

You find people who love religion, love the Jesus Prayer, spend their whole life searching for pure prayer, yet they miss the mark. I once met someone who met a monk at Mount Athos who was in a very bad state, very dark, very bitter, very angry. When asked what was the matter, he said, “Look at me; I’ve been here 38 years, and have not yet attained pure prayer.” This fellow was saying how sad he thought this was. Another man present said, “It’s a sad story all right, but the sadness consists in the fact that after thirty-eight years in a monastery he’s still interested in pure prayer.” You can make pure prayer an idol, too. Those are the worst forms of idolatry.

A person must be helped to want joy, to see that it is possible. And then what is difficult is that all of these other things have to be acknowledged for what they really are, together with all the pain that has to be experienced.

The other day a woman said to me, “It’s not enough for me to say I have to forgive my father. I can’t do that until I experience the rage and the sadness and the anger over how my childhood was. And that’s what I have been afraid to do.” Just because you know with your head that someone has offended you, that you ought to forgive them — that’s not forgiveness. But how do you achieve the actual reconciliation where you are really at peace with the other? One must experience in full the pain of the actual harm that was done. That’s the hardest part of forgiveness. That’s the block for most people. It has to be gone through again and again, and layer after layer has to come up.

When forgiveness is needed, one of the hardest things is to face the fact that the way I handled being harmed wasn’t always the best, that I have a certain responsibility for allowing myself to have been harmed. One does have to admit, very often, that there were choices for one as well. There’s always some form of symbiosis at work. That’s why Chrysostom could write that the world is filled with evil but no one can harm him who does not harm himself.

The great example for Christians would be their Christ-like martyrs who have not allowed themselves to be touched by that evil, what Evagrios calls “allowing the devil to rejoice two times.” You are sinned against; the devil rejoices. You react with vengeance or without forgiveness, and the devil rejoices two times. Never give the second joy.

So forgiveness is not just the healing of the other, it is the healing of yourself, too. If you don’t forgive, you allow yourself to be poisoned. That’s why Jesus says, “Do not resist the evildoer.” The minute that you resist or react in kind, you become part of the evil yourself. That’s the radical teaching of the Cross.

Ultimately it comes to this. We are forgiven whether we like it or not. If we accept it, then we, too, become forgivers, and it’s called Paradise. But if we don’t accept it, it is hell. When you reject the forgiveness, you destroy yourself. You refuse communion.

Source: In Communion