Father Roman, to begin, what can you tell us about the monastic way of life?

This is a good question. First, however, you have to understand the Romanian cultural environment when I was young – in the 1920s – 1950s. The Romanian people, I think, were always inclined toward the monastic way of life, because being monastic and leading a monastic type life does not mean only to go and live in a monastery. When Jesus was preaching the Gospel—“if you love your mother and father more than Me you are not worthy of Me,” or when Jesus said “if you don’t take your cross and follow Me you are not worthy of Me,” Jesus was not speaking to monks; monks did not exist at that time. Jesus was speaking to people, single people, married people, everybody. So in a way, regarding the virtues, there is no difference between monks and lay people. The monastic virtues are for everyone. I will give you an example. Those who want to dedicate their lives to Jesus, to the Church, and who want to save their souls through the monastic way of life, become at times at odds with the wishes of their parents, who may want their children to lead a secular life. But remember—God comes first in our life, then come the parents and the family.

First we must listen to God because He is the Father of all of us. So there is a monastic element in that. Abstinence, for example, is not just for monks. In general married people need to exercise more abstinence than single people. Lay people as well need to exercise more abstinence than monastics. Abstinence means to abstain from food, from alcohol, from many other things. Or, in our culture here in America, we abstain from certain things only when we are forced into it by medical conditions. But God wants us to abstain from certain things so that we are not dominated by material things; to be free of material things. The material things are temporary; we cannot take them with us. As persons we have to grow. We cease to be a person when we are dominated by material things. Sex, drugs, alcohol, smoking, overeating, and many other things like that make you a slave; you are no longer a free person. Well, God wants us to be free because He made us free and this is our likeness with God: “Let us make men according to our own image.”

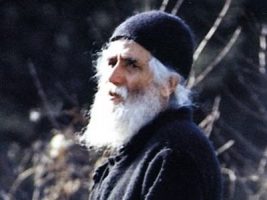

So the virtues are the same for married people as they are for monastics; The only difference is that the monastics go to a monastery, living in communities because they want to dedicate their lives to God without the social obligations. Monastics do not marry; instead they take a vow of virginity and of poverty. Why? Because they do not want to depend on possessions. Monks do not own land, do not own anything, other than their personal belongings. In the monasteries, the monks wear a habit—a special uniform if you wish—because they are considered the army of the Church, the soldiers of the Church. The Church depends on them.

As we speak today, there is a session of the OCA Holy Synod at our monastery. The Holy Synod of a Church is made up of its bishops. The Church needs bishops. The bishops cannot be married, and they should be from among the monks. If the leaders of the Church come and tell you, “we need you for a bishop,” you cannot say no because you have to be obedient to the Church. Along with the vows of chastity and poverty, the monk also takes the vow of obedience. Or if the Church needs to send you somewhere to start a church, you have to go. You don’t have possessions, a house to worry about—“Oh, I have a house, what to do with my house?” You have just a suitcase and you put in it the necessary things and immediately you go. So obedience is another vow that monks take.

As I said before, monks wear a habit. They wear long clothes and robes. This is the outer monk, the monk that everybody sees. This “outer monk,” so to speak, is not for everyone. The inner monk is for everyone. In other words, the virtues of, abstinence and sacrifice are the same for the professed monk as well as the lay person. So those monastic virtues—to deny yourself to take up your cross, to abstain—these are for everyone. The virtues are the same and we go to the same place, married people and monks. And marriage is not an easy task. One needs much asceticism in marriage. You have three, four, five children; sometime you do not even eat, just let them eat, as you sacrifice yourself for them and others. So this is the difference between monks and lay people.

Romania has about 500 monasteries. There were always many monks and nuns in Romania. They are not cloistered; they go shopping, they go to the market. Romania is a small country, the size of the state of Ohio, and monks and nuns are influenced by the culture of the country. Even now, the monasteries of Romania are full of nuns and monks. So it depends on the culture in which you live and the way you understand the Gospel.

Can you tell us what led you to the monastic life?

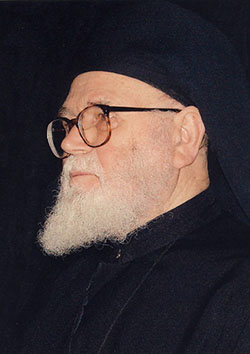

I didn’t go to the monastery when I was young. I was in prison twice, and after my first imprisonment I became a monk because I matured while in prison. When you experience suffering, then you begin meditating. I was a teacher. I was teaching in a high school in Bucharest. I was mature enough to understand life and to ask myself, “why am I not married at the age of 30?” and “should I marry or not?” So imprisonment gave me time to meditate and think, “What is better for me? Should I marry and have a family, or should I choose the monastic life?” I decided to follow the monastic life.

As a young boy I lived in a monastery, at the Seminary of Cernica in Bucharest, and I loved monastic life. So for me, monasticism was a natural way of life.

Can you talk about what it was like as a Christian to live under a communist regime?

As a Christian, you had to make many compromises. For example, you have children and they go to school. And they are told in school that there is no God, and that you do not have to pray, and that you do not have to have to wear a cross around your neck, and that you do not have to go to church. Children went home, and grandma prayed with them and making the sign of the cross. We kept this Christian life in the family. Nothing could be manifest. You were not allowed to manifest your Christian life.

What happened to the churches and monasteries under the communist regime?

The churches were tolerated because Romania was basically a massive Orthodox country. The Church was very strong, and the communist regime did not want to risk anything. Many monasteries, however, were closed. Only those that were declared historical monuments remained open, and Romanians were happy because almost all the monasteries were historical monuments. The communist regime transformed the monasteries into museums, and they kept a few monks or nuns as tour guides to keep and take care of the museums and the huge libraries and archives that the monasteries possessed. And so the churches of the monasteries were also kept open. There was, however, a decree—decree #410 —by which the communist government closed all the monasteries that are not historic monuments, forcing all monks and nuns under 50 years of age to leave the monasteries and go to work for the state. Only the old monks were allowed to stay in the monasteries to keep them open as historical monuments, and they kept the liturgical cycle of the Church—Matins, Vespers and the Divine Liturgy—and they kept all of these and took care of themselves. Because people in Romania were Christians, they went to church in the monasteries and they helped these old monks and nuns. The communists couldn’t control that, but they were not so much interested in simple folks—but they were interested especially in the intellectual class because the intellectual class creates the habits, the culture.

The communist regime persecuted the Roman Catholic Church because it was the minority faith, mostly for foreigners. Romania is 90% Orthodox, so they persecuted mostly the other denominations by taking their property and kicking them out. With Orthodoxy, they didn’t dare go too far, so they pulled out young people from the monasteries. But the old people still remained there and the churches of the monasteries were open and the liturgical cycles continued uninterrupted. During these times, monastic life was still going—it was not growing, but at least it was maintained.

How did your own struggles with the communist government impact your spiritual life?

The communists could not control what is inside of you, but you couldn’t express what you were thinking. You were unable to express your opinion, not only as a monk or priest or Christian, but as an intellectual in general. Not all intellectuals in Romania during the communist regime were communists. In order to survive, they were forced to say one thing, but they believed something else within themselves. So they led a double life. What was in their minds and souls—their convictions—was one thing, but what they expressed aloud was another. It was all a matter of survival. That was a very, very difficult life. It was not like here, where you are not afraid of anything. You are not afraid to express yourself—it was not like this. People were saying exactly what the government asked them to say in order to have a job, to be a teacher, to have a profession, to be able to provide their families with their daily bread. But what they thought and believed, the communist couldn’t control.

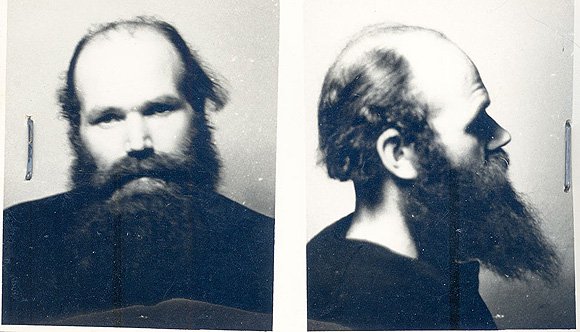

In a way, we were happy in prison. Despite all the physical tortures, they were nothing. You suffered from them, and you might even die. But communist imprisonment was worse than physical torture. They wanted to keep you at the limit of normal and abnormal, but they couldn’t control what was inside of you. In a way, for a priest, the communist prison was good because there, in prison, we were praying. Once you are convicted—of “crimes” you did not commit—you were placed in a cell; there is nothing else. They put the intellectuals—and especially the priests—in solitary confinement for at least one or two years, and in a way that was very good for us. Not having anywhere to go, or even the possibility of looking out a window because there were no windows in those cells of solitary confinement, you had to look, to go somewhere. And so you go inside yourself—inside your heart and your mind—to examine yourself, to see who you are and why God brought you into this world. You questioned whether God even exists, and wondered about your relationship with God.

When we were free, we did not have time to ask ourselves these questions. Our faith was superficial, because you can learn a lot of things and can have a mind like an Encyclopedia, full of all knowledge, but if you don’t know yourself and who you are, even if you know everything in the world, you are superficial if you don’t ask “Why do I exist?” and “What is the destiny of my life?” and “Why did God create me?” and ” If I believe in God what does God want from me?” You do not ask yourself these things when you live in freedom, because you are in a hurry to do a lot of things, to read a lot of books, and you become the slave of the books, the slave of knowledge, of concepts of philosophy, and so on. But you do not have the time to meditate on who you are. When you are free, you are made out of quotations from books. In prison, we were not allowed to have any books. In eleven years I did not see a pencil or a piece of paper or a book, and this applied not only to me, but to all the intellectuals and all the priests. The communists gave books and papers to read to simple folks because they wanted to convince them to become communists. They wanted, however, the intellectuals to be transformed into beasts, to become like animals. The interesting think is that it did not happen. Instead, you became yourself because you started to examine yourself. Once you were out of prison, they were concerned that you do not make propaganda by telling others what had happened in prison, and so on, and so many of us were expelled from the country just so we would not tell others what was going on in prison.

How did you witness Christ is prison?

In prison, most of the time you were by yourself. I also had been in a forced labor camp. In the forced labor camp, we had our groups of prayer and we had priests who heard confessions. Each priest had a group around him. We witnessed Christ more in the forced labor camp because there was not too much control there. It was a large community, and the communists were concerned about how much you worked. In prison, it was impossible to witness Christ, even if you were alone or you had a single cellmate. Sometimes there were four in the same cell, but you only talked to a small group of people. In the forced labor camps, we even had the Liturgy because we had priests, although they were celebrated without vestments and without anything else other than a piece of bread and some tonic wine that the doctors in the hospital provided. I was in a forced labor camp with 16,000 people in which there was a hospital. The doctors also were prisoners, so they provided tonic wine for us for the Liturgy, and we spared two pieces of bread from breakfast. The guards did not know we celebrated the Liturgy; as they were passing by, they thought we were just babbling. I remember in prison though, a priest had Liturgy under a blanket in his cell. When the guard entered, the priest covered everything with the blanket.

Why is suffering important as a Christian?

Suffering is good, not only for Christians, but for everyone, because if you do not suffer, you do not understand anything. Suffering is a good experience. And in the Scriptures it says that suffering is a sign that God loves you. In the Epistle to the Hebrews, chapter 13, Saint Paul says that if you do not suffer, you are not children of God. What father does not chastise His children? He punishes His children because He loves them. If you do not suffer, you are not the sons of God. After you experience suffering, you understand more—and better—things in this world, much deeper than those who do not experience any suffering. So suffering matures you in your spiritual life. You should not avoid suffering, but you should not look for it. God takes care of that. There is a lot of suffering in the world. So many families have children in the hospital—my doctor has an eleven-year-old daughter with bone cancer. What suffering is felt by that family whose daughter may be dying. We ask ourselves why?

God allows the world to have beggars and crippled people, and all this is because we otherwise would not be able to be charitable. We have to exercise our love because love is not just a word, but it is something that we must do. And you do things for those who need them. So that is why there are orphaned children and crippled people and so many other sufferings which enable us to exercise our love for our neighbor, because Jesus teaches us to love God with your whole heart and whole mind, but to love your neighbor as you love yourself. But if my neighbor does not need my love, what is love? Just a hand shake? That is not love. Hugging another person? That is nothing. Go and take a crippled person on the street and give him a hug and ask him what you can do for him? That is love. Do not live for yourself. Live for others and always to deny yourself. Forget yourself and remember that others exist. That is the Christian life. Do not say, “what about me, and myself, and I?” Who are you? You are nobody. Try not to pay too much attention to youself. But when you ask, “can I do something for you, maybe you need me,” then you embrace meaningful Christian love. So suffering in this world is permitted by God so that other Christians might concentrate their love on those who suffer and do something for them, sacrificing themselves for others. In our own life, suffering is permitted, so we understand why Jesus was crucified.

I am able to forgive. I pray for the guards who tortured us in prison. I am not against them because I understand that they were forced to do that. And you forgive only when you suffer. When you do not suffer, you do not want to forgive, and then you are condemned. There was a movie maker who came and made a movie with me and Father Calciu. The interviewer said, “how can you forgive them?” Well, why not?! They are created in the image of God. We know that in that kind of regime they were forced to kill us, to torture us, to do what they were told to do, otherwise their families would not have bread to eat. You are able to forgive when you suffer. When you do not suffer you are not able to forgive. You say, “no, no, no, you should not do such and such a thing, and if you do, you should be punished because you did it.” So suffering is very important in Christian life.

How does life in America differ from your experience in Romania?

I thought I came to a free country. And that is true; you have the freedom to do anything you want, so long as you do not to hurt anybody. If you hurt anybody, for sure you have to suffer the consequences. Speaking of freedom of conscious and thought, I doubt that we are free, because by being free to do everything you can destroy yourself if you are not mature. Freedom without responsibility is not freedom. Only when you are prevented from doing what you want to do can you understand freedom. But when you say, “I want to do everything I want,” you are not free. Think about Genesis, the first book in the Bible. When God created man, he did not understand what freedom was until God told him, “you cannot touch this tree—it is the tree of the knowledge of good and evil.” So if God created man to be free, then ask yourself why He gave him a limit—“do not touch this.” Without this limit, man cannot understand what freedom is. Freedom is just a word if you do not have restrictions. So freedom without discipline is not freedom. And many in America think that they do not have to respect anyone and that they are free to do everything. This is not freedom.

What are some ways we can find Christ today, in American society?

Well, first of all, Christ is in you. Christ is not just some nice guy. He is God, and God is within you. God is in our consciences, in our hearts, in our minds. He is not something material you see outside of yourself. You find God in yourself. You descend in your personality. We are eternal, we never die, the body goes to the cemetery but the conscience, the person, is continually alive. So when you descend into yourself, your conscious is infinite. And this infinity is the temple of the Living God. Saint Paul says many times that you are the temple of the Living God because God lives within you. You find God when you know yourself, when you know who you are. If you neglect that, when you say, “I don’t have time to think about myself,” you will never find God, because God is not something material. You do not find him in a specific place. God is always with you if you want Him to be with you. You find God when you find yourself. “Who am I?” Pay attention to these verses of the Scriptures—“you are the temple of the Living God because God lives within you,” and as Jesus said, “remain in Me and I in you. I am the vine and you are the branches,” and if you do not remain in me you do not have the sap to feed yourself, and you will dry up. People who complain that they do not feel God are dry branches. They have to remain in Christ and to accept Christ by saying, “Lord, come, I am here. You created me. Open my heart because You created this heart. You created the door, enter please.”

You have to talk with God wherever you are—even while walking along the street or driving your car you can say, “Lord, You are in the front seat, and I know that You are here. Tell me, why did You create me?” You have a lot of things, an infinite number of things, about which to converse with God, and God wants you to talk with Him. Prayer is not about how much you read from the prayer book, or how long you kneel; prayer is your whole life. When you eat, when you drink, when you drive a car, when you discipline your children, you are in a state of prayer. Life is a Liturgy. It is not only in the church that the Liturgy takes place; the Liturgy is outside the church building too. The entirety of life should be a Liturgy—if you feel the existence of God. But you have to get that feeling of the existence of God. How? I always say, especially to young people, “have a dialogue, a permanent dialogue, with God. Sure you are busy—you eat, you prepare your exam if you are a student, you work and you are very busy, but always say, “Lord I know You are here; I didn’t forget You. Look at me and do not abandon me.” Many times, this permanent dialogue with God becomes a prayer, because prayer is communication between man and God.

Prayer is not something you do for a short time, after which you say, “I finished my prayer.” You never finish your prayer. The definition of prayer is this: the feeling of the presence of God in you. And if you have this feeling of the presence of God, you engage in a continual prayer. If you pray only at appointed times, you don’t pray at all, said one of the monks. So pray all the time, because prayer is not “give me, give me.” Prayer is saying “I love You and I want to spend time with You.” Ask something of God, and don’t worry whether God is answering you, even if you don’t think He is. He’s giving you good hints and good suggestions on how to resolve your problems. So to find God in our culture here is to be conscious that God exists, that He exists not outside of yourself, but inside. God is always with you.