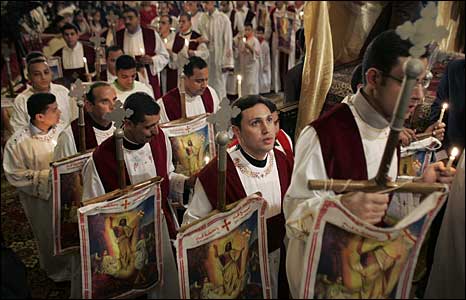

It seems that the dust in Egypt doesn’t want to settle. After the fall of Mubarak’s regime, a series of consecutive breath-taking developments are still reshaping the face of the most populous country in the Middle East. Any expectations that arise today will probably be vaporized the next day. This is the current situation in every aspect of life in Egypt, including the fate of more than 10 Million Christians who are facing escalating challenges due to the fast growing power of radical Islamist political groups.

After the overwhelming scenes coming from Tahrir square depicting Christians and Muslims unified and protecting each other, Christians left the romantic dreams of national unity behind to face the real situation in order to face the accumulation of more than 60 years of a radical religious speech generated by fundamentalism in Egypt.

A few weeks after the Mubarak’s resignation, a church in Helwan near Cairo was burnt to ashes. A few days later, Islamists made attempts to begin enforcing their version of Sharia (Islamic law) in remote villages and the first case was cutting off the ear of a Copt in Upper Egypt. Furthermore, a new mayor for Qena governorate was appointed by the new government, this major is Christian. Having a Christian mayor led to massive protests by Muslims of the governorate. The protesters blocked train lines and threatened the government itself.

The problem is that the High Military Council, which took over Egypt after Mubarak’s stepping down from the presidency, dealt with the situation at arm’s length. Questions, and justifiable doubts, are being raised about the reason for having radical Islamists and formerly forbidden groups in the political scene today. An axiomatic explanation would suggest that the fall of Mubarak, who was allegedly a secular president, released the potential radical monster. This explanation cannot be sustained in the face of the study of chronological developments of communal violence in Egypt since the coming of Sadat “the faithful president” in the 70’s until the bombing of the Saints Coptic church in the 2011 in the early hours of New Year ’s Day.

Since Sadat, Mubarak’s predecessor, released Islamists from jail and supported them Egypt became vulnerable to the spread of radical Islamic ideology. After Sadat’s assassination by the very same Islamists he released from prison, Mubarak played a tricky game of hunting many birds with one stone. He kept the Islamists’ presence as a scarecrow to the western world in order that they would overlook corruption and oppression practiced by his regime for 30 years. This threat was also used with Copts in order to show them that Mubarak is their protector and consequently they must vote for him. The presence of the Islamists was strong but controlled according to the domestic political deals with the formerly ruling National Democratic Party in Egypt. Today, the ruling party has vanished and no deals can bind the Islamists’ strategy. Egypt became a land of chances for the radical Islamists who were made by Mubarak’s regime and news sources reported that more than 3500 Islamists returned to Egypt.

Three brand new parties representing the political Islam spectrum have now been established to create a channel for the Islamists to take over the parliament. The first test of the power of Islamists was the recent referendum over the fate of the former constitution. Liberal political movements who made the revolution along with Christians said “No” while Islamists said “Yes” to guard the Islamic identity of Egypt crafted in the old constitution. The latter achieved a striking victory of around 80%, after they used religious pulpits to raise the slogan, “Islam is in danger. Say yes to Islam”

The basic problem now is that the High Military Council, which is temporarily in charge, is working at arm’s length. The presence of people like Abboud el-Zomour, who assasinated former president Sadat, in media and public events suggests that Egypt accepts them as a status quos and this threatens Copts. On the other hand, Christians today in Egypt are standing at a crossroads, either stepping back to the strategy of a shrinking Christian contribution within the Church walls, or actively participating in the political battle field to defend their rights.

The promising participation of liberal parties is carefully watched by Copts who must push democratic and civil state demands forward in order to face the Islamist wave that calls for treating Copts as a second class citizens. The manifestos of some of the emerging parties are clearly calling for advocating the principle of citizenship and equality that goes beyond gender or religion divisions. Free Egyptians is the name of a new party established and funded by a Christian businessman, Naguib Sawirus, is calling for citizenship and civil state.

The main challenge facing Christians is to take the right step amidst all these changes. Some are calling for a Coptic parliamentary quota system to guard their political representation. However, this is difficult in a country like Egypt which doesn’t have a geographical distinction between Christians and Muslims. The only way out for Copts is to go to the street and support liberal parties as Egyptians, not Christians. Citizenship and a civil state is required for the future of Egypt. To achieve it, ten million Christian Egyptians must call for their rights and for the future of Egypt without any ecclesiastical or religious limits to their ambitions.

Minas-monir@live.com

Minas Monir is a UK – based journalist, researcher and writer. The author of several published studies on Theology, he is also an expert on Egyptian affairs and political theology. He is currently a Desk Editor at The Majalla, a magazine specializing in Middle East affairs and is also an MA candidate at Cambridge Theological Federation.