|

Last Updated: Feb 8th, 2011 - 05:50:02 |

Source: IN COMMUNION / FALL 2010/ issue 58

|

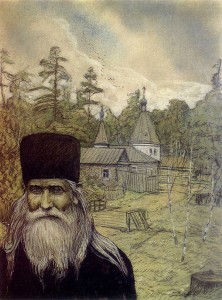

| Elder Zosimas: an illustration for The Brothers Karamazov |

How can one believe in a loving God who allows the innocent to suffer? I’ve been asked this many times, and I’ve never been quick to answer. Subconsciously, I’ve probably asked much the same thing in the past.

While I may not frame the matter this way now, it remains a useful question, if only because it reveals a premise I am no longer willing to buy – the illusion of individual autonomy.

The question reveals a keen ignorance regarding how intimately we are connected to one another – both now and forever – and more or less ignores the extreme freedom that God appears to insist upon in creation. These phenomena, together, provide a clue as to why all this suffering isn’t exactly God’s doing.

Sooner than later, we’ll want to puzzle over God’s curious insistence on the radical freedom of creation – its inhabitants and the volatile earth itself; but for now, let’s attend to the business of our intimate connection with one another and to the suffering caused by human failure.

I dare say that if the innocent suffer they do so because one of us – you or me or some other thug – now or in the past has set their pain in motion. If the innocent continue to suffer they do so because we have yet to take responsibility for their pain; we have yet to take sufficient responsibility for their relief.

Our failure to appreciate the degree of our own responsibility enables our famous indifference to those who suffer, allows us a continuing, dim-witted, and blithe condemnation of those in pain or in poverty. We suspect that something has caused their situation, but our failure to see our own hands in the mess leaves us thinking those suffering are somehow to blame. We shake our heads as we stand by or as we turn away, feeling both helpless and – assuming that we’re not completely dead yet – a little culpable.

That faintest whiff of our own culpability is subtle evidence that there may be hope for us yet.

In The Brothers Karamazov, Dostoevsky’s Father Zosimas manifests a keen sense of this culpability. “There is only one salvation for you,” he says to his gathered brotherhood. “Take yourself up, and make yourself responsible for all the sins of men. For indeed it is so, my friends, and the moment you make yourself sincerely responsible for everything and everyone, you will see at once that it is really so, that it is you who are guilty on behalf of all and for all.”

And there is an even greater consequence that Zosimas would alert us to: “Whereas by shifting your own laziness and powerlessness onto others, you will end by sharing in Satan’s pride and murmuring against God.”

You might even join the grim chorus of those who cannot believe in a God who would allow such things.

In the midst of his own suffering unto death, the elder Zosimas makes clear his sense of this great mystery of our mutual complicity:

Remember especially, that you cannot be the judge of anyone. For there can be no judge of a criminal on earth until the judge knows that he, too, is a criminal, exactly the same as the one who stands before him, and that he is perhaps most guilty of all for the crime of the one standing before him. When he understands this, then he will be able to judge. However mad that may seem, it is true. For if I myself were righteous, perhaps there would be no criminal standing before me now.

In his book about the life and witness of his own spiritual father, St. Silouan the Athonite, Archimandrite Sophrony, a modern-day ascetic, further recovers for us this ancient understanding when he writes:

Sin is committed first of all in the secret depths of the human spirit but its consequences involve the individual as a whole. …Sin will, inevitably, pass beyond the boundaries of the sinner’s individual life, to burden all humanity and thus affect the fate of the whole world. The sin of our forefather Adam was not the only sin of cosmic significance. Every sin, manifest or secret, committed by each one of us affects the rest of the universe.

My time with the fathers and mothers of the Church has made clear to me the truth that my own sin is not only about me. The general consensus would have it that your sin is not only about you either. Every choice that separates us from communion with God, and every decision that clouds our awareness of His presence, or erodes our relationships with one another, has a profound and expanding effect – as the proverbial ripples in a pool.

That profound effect is to give us precisely what, by so choosing, we prefer over communion with God, what we prefer over our cultivating an awareness of His presence, and over our having healthy relationships with one another – namely, ourselves alone.

Ourselves alone, it turns out, is a circumstance that must finally be appreciated as the antithesis of our becoming human persons. The very notion of the Holy Trinity (in Whose image we are made) should lead us to suspect that personhood requires relationship, that genuine personhood depends upon it.

My hope for healing, therefore, lies in my becoming more of a person, and more intimately connected to others. To succeed as we are called to succeed, we must all come to share this hope.

Satan himself (should we say, rather, itself?) proves an exemplary case in point. In Satan, we have a figure of one who has doggedly opted for isolation, for nonbeing, and for acute (albeit a comically moot) independence. Except for the Book of Job – another perplexing study in affliction – we do not find much about Satan in the scriptures. A good bit of our “Satan” has come to us by way of Milton’s epic poem, Paradise Lost, rather than from Scripture. That isn’t to say the Miltonic construction isn’t useful to our thinking; Milton took his theology seriously. One revealing passage occurs in Book IV, where Satan speaks thus:

So farewell, hope; and with hope farewell, fear;

Farewell, remorse! all good to me is lost;

Evil, be thou my good;

By thee at least Divided empire with Heaven’s King I hold,

By thee, and more than half perhaps will reign;

As Man ere long, and this new world, shall know.

With a bit of dramatic irony, Milton offers up a Satan who – even in the midst of his strenuous denial of God’s authority – fails to notice how his own moral economy (in which God’s evil becomes Satan’s good) nonetheless depends upon God’s having established the prior economy in the first place.

With a keen sleight of the poetic hand, evil is revealed as merely a denial of the good, an absence of the good, and nothing of itself – nothing, really, beyond spiteful, infernal response.

Early in the 7th century, the beloved St. Isaac had already come to a comparable conclusion concerning the figure of Satan, and also came to understand the ontological status of sin, of Gehenna, and of death as similarly vexed:

Sin, Gehenna, and death do not exist at all with God, for they are effects, not substances. Sin is the fruit of free will. There was a time when sin did not exist, and there will be a time when it will not exist. Gehenna is the fruit of sin. At some point in time it had a beginning, but its end is not known. Death, however, is a dispensation of the wisdom of the Creator. It will rule only a short time over nature; then it will be totally abolished. Satan’s name derives from voluntary turning aside from the truth; it is not an indication that he exists as such naturally.

In his translation of the above, Sebastian Brock puts it even more plainly: “‘Satan’ is a name denoting the deviation of the human will from truth; it is not the designation of a natural being.”

One might say further that “Satan” is not the name of natural being, period.

It is the name for that which rejects being, that which is satisfied to become aberration. It is necessarily the name for that which, turning away from the natural, the good, and the beautiful – and away from the God whose communion gives life to all things – has turned, instead, toward its own isolation, severance, and death.

So much for Satan.

Writing in the 14th century, St. Gregory Palamas made a similar observation regarding the nature of evil: “It should be remembered that no evil thing is evil insofar as it exists, but insofar as it is turned aside from the activity appropriate of it, and thus from the end assigned to this activity.”

As both St. Isaac and St. Gregory Palamas are eager to establish, while sin is to be understood as nothing of itself, it can be quite something in terms of its effects. Admittedly, our particular English noun, sin, can be misleading, given that, generally speaking, when we bother to put a name to a thing, we expect that thing to exist. The Greek precursor, amartía (literally, missing the mark), is a good deal more instructive for our apprehending the status of things; the Greek word’s construction, beginning with that familiar a – which is to say, beginning with not – attends to sin’s ontology, its originating energy. It is the great not, the infernal no to God’s eternal yes. It is ever and always mistaken. Dissing the marker, it misses the mark. It is the failure – the refusal – of being, plain and simple.

Those of us who struggle with habitual sins – and we know who we are – are very likely to break our hearts over the business of turning away from those chronic mark-missings. Our problems with recurring sin, and the more general human problem of being enslaved by sin, is never solved simply by our rejecting that sin, no matter how many times we try, no matter how strenuously we struggle to reject it.

This is because merely rejecting sin – that is, focusing on not sinning – is finally just another species of infernal no. “Just say no” is an insufficient principle.

The strongest man or woman in the world is not nearly strong enough to triumph over his or her sin simply by saying no to it. What we need is the strength-giving grace occasioned by our saying yes to something else, by our saying yes, and yes, and yes – ceaselessly – to Someone else.

It is not finally our turning away from sin that frees us from sin’s recurrence; rather it is the movement of our turning toward Christ – and the mystery of our continuing turn into Him – that puts sin behind us.

One other illustration comes to mind. Orthodox Christians generally observe three fasting seasons during the year besides Great Lent; many also observe most Wednesdays and Fridays as discrete days of fasting throughout the year. These are days when, for the most part, neither meat nor dairy foods are eaten. In any case, the tradition is keen to insist that fasting be accompanied by almsgiving. One forgoes expensive foods in favor of inexpensive food, and one is encouraged to share with the poor whatever money is saved by eating on the cheap. Not to put too fine a point on the matter, the tradition teaches us that a fast – or any manner of self-deprivation – that is not accompanied by good things done for others is understood to be “a Satanic fast.”

Forgive my inserting more poetry to bring home the point. This particular piece is one of a sort of playful, mostly serious series of poems having to do with word studies in New Testament Greek; in this case the word is metanoia.

Repentance, to be sure,

but of a species far

less likely to oblige

sheepish repetition.

Repentance, you’ll observe

glibly bears the bent

of thought revisited,

and mind’s familiar stamp

– a quaint, half-hearted

doubleness that couples

all compunction with a pledge

of recurrent screw-up.

The heart’s metanoia,

on the other hand, turns

without regret, turns not

so much away, as toward,

as if the slow pilgrim

has been surprised to find

that sin is not so bad

as it is a waste of time.

The good, on the other hand, is what actually exists; our long and continuing tradition tells us that all that is worthwhile is good, and all that is good is worthwhile. Moreover, all that partakes of the good is by good’s efficacious agency brought into existence, and is by that selfsame agency kept there.

Regardless of our situations, we are inevitably partaking of something or other at every moment. The catch is that we will either partake of what is, or we will partake of the absence of what is. We partake either of life (all that has true being by way of its connection to God) or of death (all that has opted to sever that connection).

As we all must have guessed by now, we actually are what we eat.

Scott Cairns is an Orthodox poet, memoirist, libretist, and essayist. He serves as a reader at St. Luke Orthodox Church in Columbia, Missouri. He is also a professor of English, Director of the Center for the Literary Arts and director of the Creative Writing Program at the University of Missouri.